There are a few ways to answer the question: Why liberty? There is, of course, Jefferson’s answer: That everyone is born with a right to liberty is self-evident. Not as in ‘obvious’, but as in ‘requiring no justification’.

Of course, what’s self-evident to one person isn’t necessarily self-evident to another. So this doesn’t have a lot of persuasive power. The fact that Thomas Jefferson would prefer dangerous liberty to peaceful slavery doesn’t offer any reason why you should have the same preference.

Libertarians often answer the question by claiming that liberty is the best means to some other end. A friend recently expressed this by saying: ‘If human freedom flourishes you always get the best outcomes in the shortest amount of time.’

But does this mean that if something other than liberty could provide better outcomes, they would be willing to give up liberty? I don’t think they believe this, even though it’s what they’re saying.

I think they actually believe that liberty is valuable as an end in itself, and they’re just making the ‘liberty leads to better outcomes’ argument because it seems more practical, and more easily understood.

But the first problem with this is that other people are making the same claim — that their schemes will ‘lead to better outcomes’. This removes the moral component from the debate, and reduces it to a kind of transaction: Give us liberty, so we can have more of something else. Which is a tough sell, because the competition is promising the same benefits, but without requiring the kind of personal responsibility, to say nothing of risk, that comes with liberty.

The second problem with this is that ‘the best outcomes’ isn’t a sensible concept, unless you believe that everyone has the same values, and prioritizes those values in the same way.

‘Best’ is always ‘best for’ someone or something (in the same way that ‘essential’ is always ‘essential to’ or ‘essential for’ someone or something). Outcomes that are better for some will be worse for others, for the simple reason that we don’t all desire the same things.

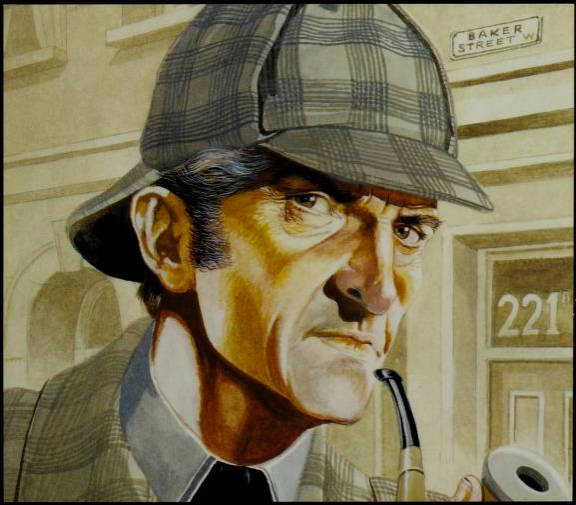

This brings us to a third answer — the one I prefer — which is loosely based on Sherlock Holmes’s observation that once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.

Every other organizing principle for society begins by denying this fundamental truth about humans: You don’t know what’s best for me, and I don’t know what’s best for you. And so every other organizing principle is doomed to the kind of failure that must inevitably follow from building on a foundation of falsehood.

Eliminate the impossible, and what remains, however improbable… is liberty.