This is the second part of a two-part article explaining how the Sununu administration and the New Hampshire Department of Education (DOE) colluded to use COVID-19 to secretly eliminate limits on the remote education of children in the state.

In the first part, I described the existing legal requirements for public education and how DOE made an illegal “emergency” amendment to its rule limiting remote instruction in New Hampshire public schools. In this second part, I will explain how DOE attempted to justify this illegal change, the fact that Governor Sununu knew about it, and how this change has impacted children in New Hampshire.

DOE Admitted Its Rule Change Was Illegal But Tried to Justify It Anyway

A brave father in Salem, New Hampshire, hired me to challenge the closure of New Hampshire public schools in May 2020. His daughter – then a sophomore and star athlete attracting collegiate attention – stood to lose a lot from the school closure and cancellation of her season. We filed suit later that month. (The judge who addressed our request for an immediate injunction labeled our filing “wholly inappropriate” and then scheduled it for hearing in early June 2020.)

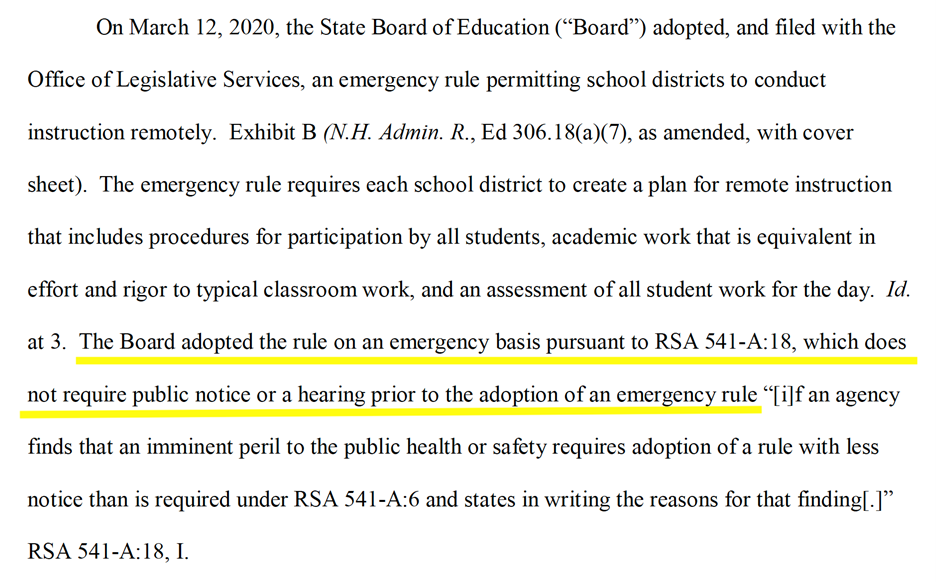

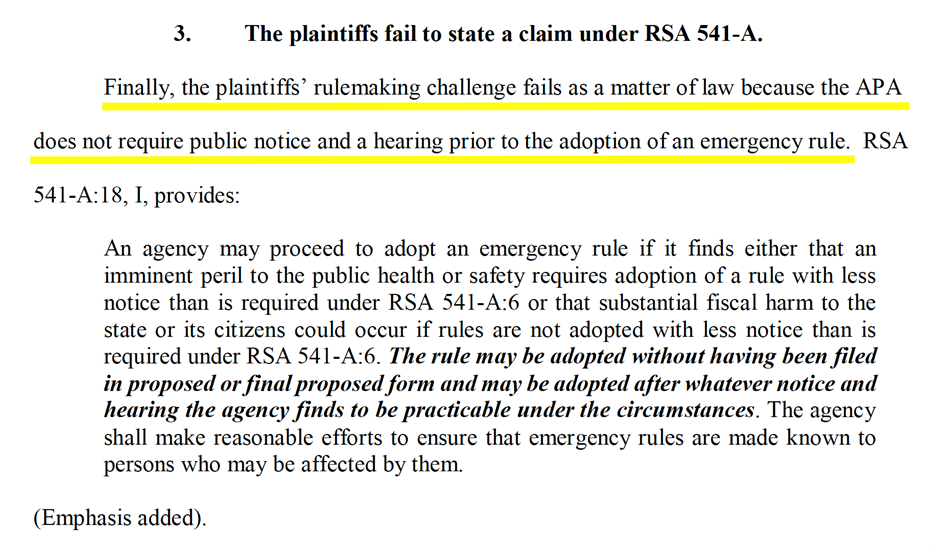

At that hearing, DOE conceded it did not file or otherwise provide notice of the proposed “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) or a hearing before its adoption. Rather, it arrogantly attempted to justify its conduct. It argued publishing notice of the proposed amendment and a hearing was not required under the “emergency” rulemaking requirements in RSA 541-A:18, I.

That is, of course, preposterous. As I explained in the first part of this article, RSA 541-A:18, I states “[a]n agency may proceed to adopt an emergency rule if it finds either that an imminent peril to the public health or safety requires adoption of a rule with less notice than is required under RSA 541-A:6 or that substantial fiscal harm to the state or its citizens could occur if rules are not adopted with less notice than is required under RSA 541-A:6. The rule may be adopted without having been filed in the proposed or final proposed form and may be adopted after whatever notice and hearing the agency finds to be practicable under the circumstances. The agency shall make reasonable efforts to ensure that emergency rules are made known to persons who may be affected by them.”

DOE claimed the second bolded phrase above meant that, because “notice and hearing were not practicable” with ED 306.18(a)(7), they were suddenly “not required.” Here is that argument from page 7 of its brief that it filed in court . . .

. . . and from page 34 . . .

This strained interpretation of RSA 541-A:18, I – and I credit then-Solicitor, General Daniel Will, for a valiant effort in explaining it – ignored four key pieces of the statute.

First, the bolded language above does not say an agency may dispense with notice and hearing when adopting an emergency rule. Rather, it states an amendment to a rule may be adopted “with less notice than is required under RSA 541-A:6” and “after whatever notice and hearing the agency finds to be practicable.” RSA 541-A:6 requires “at least 20 days’ notice” for a proposed non-emergency change to a rule. The bolded language above requires “less notice than” that or “whatever notice and hearing” an agency deems “practicable,” NOT “no notice and hearing” or “without notice and hearing.” According to a dictionary, the word “less” means “constituting a more limited number or amount,” “of reduced size, extent, or degree,” or “more limited in quantity.” The word “whatever” means “any” or “of any kind at all.” DOE’s interpretation construes both words to mean no notice or hearing at all. This interpretation added language to the statute that was not there or replaced language that was not there with DOE’s own, more convenient, wording.

Second, DOE’s interpretation ignored the word “after” that precedes the phrase “whatever notice and hearing” above. The word “after” means “following in time or place,” “behind in place,” “subsequent to in time or order,” “subsequent to and in view of,” or “later in time.” The combination of the word “after” with the words “whatever notice and hearing” indicates an agency must provide some notice and opportunity for a hearing of the proposed rule before it may adopt it. Otherwise, under DOE’s interpretation (which eliminated the requirement of notice or hearing altogether), the word “after” would be superfluous.

Third, DOE ignored the first part of the second sentence in the statute: “The rule may be adopted without having been filed in proposed or final proposed form and may be adopted after whatever notice and hearing the agency finds to be practicable under the circumstances.” That portion of the sentence includes two elements of RSA 541-A:3, which identifies the seven rulemaking requirements for the adoption of a rule. If you recall from above, RSA 541-A:3 states, “[e]xcept for interim or emergency rules, an agency shall adopt a rule” by a seven-step process:

- Filing a notice of the proposed rule under RSA 541-A:6, including a fiscal impact statement and a statement that the proposed rule does not violate the New Hampshire constitution, part I, article 28-a;

II. Providing notice to occupational licensees or those who have made timely requests for notice as required by RSA 541-A:6, III;

III. Filing the text of a proposed rule under RSA 541-A:10;

IV. Holding a public hearing and receiving comments under RSA 541-A:11;

V. Filing a final proposal under RSA 541-A:12;

VI. Responding to the committee when required under RSA 541-A:13; and

VII. Adopting and filing a final rule under RSA 541-A:14.

RSA 541-A:18 I, certainly relaxes the requirements for rulemaking in “emergency” situations, but it does not dispense with all of the requirements. The first part of the second sentence in RSA 541-A:18, expressly omits two of those seven requirements above: “The rule may be

adopted without having been filed in [1] proposed or [2] final proposed form.” The first requirement (“filed in . . . proposed . . . form”) refers to the requirement in RSA 541-A:3, III (“Filing the text of a proposed rule”), and the second requirement (“filed in . . . final proposed form”) refers to the requirement in RSA 541-A:3, V (“Filing a final proposal”).

The inclusion of those two requirements in that portion of the second sentence is significant. There is a rule of construction for statutes called expressio unius est exclusio alterius, which means “[n]ormally the expression of one thing in a statute implies the exclusion of another.”

The first part of the second sentence in RSA 541-A:18, I (“The rule may be adopted without having been filed in proposed or final proposed form and may be adopted . . . .”) lists those two rulemaking requirements identified in RSA 541-A:3 that the legislature omitted from the rulemaking procedure for adopting an “emergency” rule. That portion of the sentence did not include any other rulemaking requirements from RSA 541-A:3. Thus, under the rule of construction above, it should be read to state that only those two rulemaking requirements are omitted from the emergency rulemaking process in RSA 541-A:18. Reading it to include (i.e., omit) other rulemaking requirements (such as notice and a hearing) would require adding language (the notice and hearing requirements) to it that was not included when the statute was drafted. Indeed, the second part of that sentence confirms this point: as demonstrated above, it expressly states an amendment to a rule may be adopted “after whatever notice and hearing the agency finds to be practicable.” If the legislature saw it fit to include the requirements of notice and hearing among the requirements it wanted to omit for purposes of the emergency rulemaking process, it would have included them in the first part of that sentence, e.g., “The rule may be adopted without having been filed in proposed or final proposed form, or filing a notice of the proposed rule, and may be adopted . . . .” The legislature did not, however, include those requirements in that portion of the sentence. DOE should not have interpreted in that way, either.

Fourth and finally, interpreting RSA 541-A:18, I, to require an agency to provide some notice and hearing regarding a proposed emergency rule change is further bolstered by that section’s final sentence: “The agency shall make reasonable efforts to ensure that emergency rules are made known to persons who may be affected by them.” That sentence alludes to the agency providing the public with notice of the proposed rule change in some form or another, so long as the agency “make[s] reasonable efforts to ensure” it is “made known.”

DOE failed to follow rulemaking procedures in RSA 541-A:18, I, which required that it file notice of the proposed rule despite the existence of an “emergency,” because it admits it did not file the required notice or otherwise provide it in some other manner. The Court, at the time, should have declared the “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) void and unenforceable. It did not.

Are you paying attention yet?

Governor Sununu Was Aware of DOE’s Illegal Rule Change

Well, it gets worse. Governor Sununu was obviously aware of this illegal “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) at least three days earlier: On March 15, 2020, he referenced it in Emergency Order #1. You will recall that Emergency Order #1 directed school districts to “develop a temporary remote instruction and support plan pursuant to emergency rule ED 306.18(a)(7).” (You will also recall, as I explained in the first part of this article, that DOE did not communicate this emergency change to the public until March 18.)

Governor Sununu’s knowledge of the existence of the “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) several days before DOE communicated it to the public, particularly so he could include it in Emergency Order #1, also suggests he or his office may have coordinated with DOE in pushing for the “adoption” of the “emergency” amendment without regard for the rulemaking process.

Without this “emergency” amendment, it would have been impossible (and illegal, not that it matters, apparently) to direct school districts to implement remote instruction for more than five days. (Alternatively, Governor Sununu could have attempted to suspend ED 306.18(a)(7) pursuant to the emergency powers he acquired under RSA 4:47, III, by declaring a “state of emergency,” but he chose not to do so.) Instead, someone in the Governor’s office and/or DOE determined (in shortsighted fashion) that an “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) needed to be pushed through as soon as possible, without notice, so Emergency Order #1 could be issued immediately.

DOE’s Attempt to Amend its Illegally-Amended Rule

Perhaps believing it could escape culpability for this blatant circumvention of the rulemaking process, DOE then attempted to propose a change to the “emergency” version of ED 306.18(a)(7) above, as if it had been validly adopted.

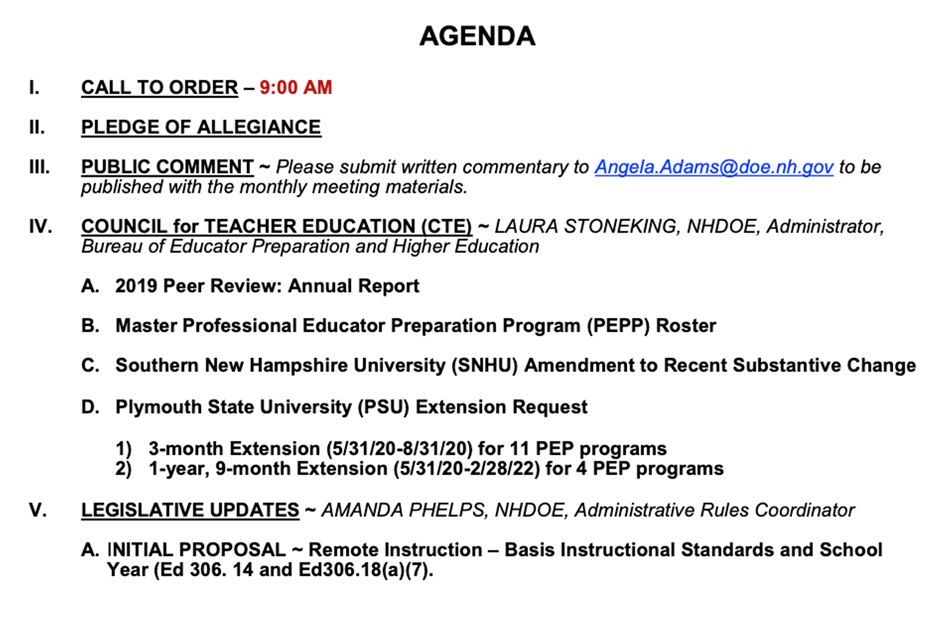

DOE posted its Agenda and Meeting Materials for its May 14, 2020, meeting. The Agenda listed an “initial proposal” for ED 306.18(a)(7):

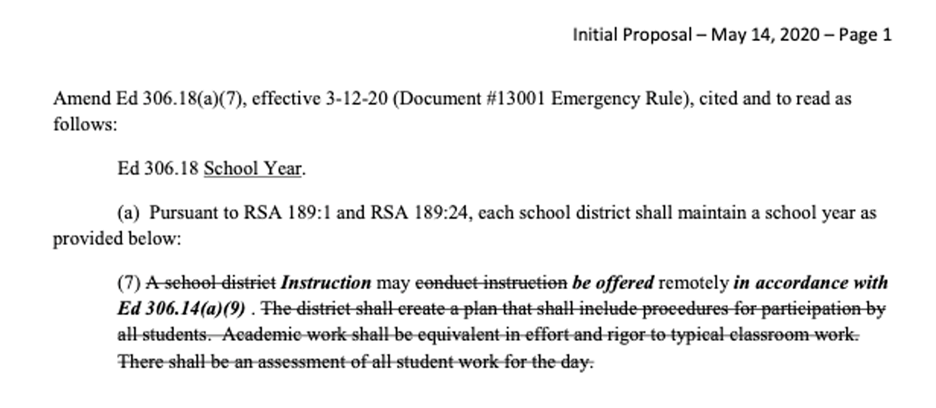

The proposed change to ED 306.18(a)(7) then appeared in the Meeting Materials for the May 14 meeting:

There were four problems with the above proposal.

First, as noted above, it purported to modify the emergency version of ED 306.18(a)(7) that was purportedly “adopted” on March 12 in contravention of rulemaking procedures, not the original version of the rule.

Second, it appeared very similar in format (i.e., a draft proposal with strikethrough and italicized and bolded insertions) to the “emergency” amendment DOE claimed it adopted on March 12.

Third, if adopted as written above in May 2020, this new version of ED 306.18(a)(7) would have allowed remote instruction year-round. I warned the Court about this in the lawsuit we filed, but my concerns were summarily dismissed. But that is EXACTLY what happened: in the fall of 2020, many school districts implemented remote-only or “hybrid” (remote and in-person) schedules. Emergency rules are effective for only 180 days. This proposed change would have made it permanent.

Fourth, since it appeared to be a proposal for a normal rule, not an emergency rule, DOE had to comply with the rulemaking requirements in RSA 541-A:3, such as providing 20 days’ notice of the proposed change, etc. Once again, it failed to do so: DOE did not appear to have provided any notice of the proposed change above to the “emergency” version of ED 306.18(a)(7).

Despite DOE’s egregious rulemaking errors and Governor Sununu’s knowledge of the illegal “adoption” of this “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) before the public was aware, Governor Sununu and DOE proceeded with this brand new requirement – passed under cover of night – for open-ended remote instruction in New Hampshire public schools.

The “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) was eventually made permanent. It remains that way today: there no longer exists any limit on remote instruction in New Hampshire public schools.

Governor Sununu’s Subsequent Emergency Orders Perpetuated Remote Instruction

On March 27, 2020, Governor Sununu issued Emergency Order #19. That Order extended the period of remote instruction another month: “All public K-12 school districts within the state of New Hampshire shall maintain their provision of temporary remote instruction and support, which began pursuant to Emergency Order #1, through Monday, May 4, 2020.”

Despite the invalidity of the emergency rule above, Governor Sununu again did not suspend, let alone mention, ED 306.18(a)(7), or the requirements of RSA 189:1 or RSA 189:24.

Governor Sununu then extended his “state of emergency” declaration several times: on April 24, May 15, and June 5, 2020, he issued Executive Order 2020-08, Executive Order 2020-09, and Executive Order 2020-10, respectively, which collectively extended his declaration of a “state of emergency” until June 26, 2020. Those Orders also extended all of his Emergency Orders.

By the time we filed suit in May 2020 challenging the school closures, Governor Sununu had issued an astounding 49 Emergency Orders addressing a wide range of topics and areas to combat the Coronavirus. (By the end of the pandemic, Governor Sununu had issued over 100 executive and emergency orders covering virtually every aspect of the New Hampshire economy.)

A Recap and the Impact of the Rule Change

Let’s quickly recap:

- Before COVID, one of DOE’s rules (ED 306.18(a)(7)) limited remote instruction to five days per school year.

- On March 12, 2020, the day before the Governor first declared a state of emergency (March 13, 2020), DOE claimed it “adopted” an “emergency” amendment to that rule that removedthat five-day limit.

- This “emergency” amendment paved the way, two days later on March 15, 2020, for the Governor to issue Emergency Order #1, the first of three Emergency Orders ultimately directing school districts to implement remote instruction for the remainder of the school year.

- In “amending” ED 306.18(a)(7), however, DOE did not follow rulemaking procedures required by RSA 541-A and its own rules (ED 214.01-06): DOE failed to provide notice to the public of the “emergency” amendment or address it at a public hearing.

- Instead, DOE first communicated this “emergency” amendment to the public on March 18, 2020, six days after it claims it was adopted, when it published it on its website.

- Making matters worse, Governor Sununu was obviously aware of DOE’s secret and illegal “adoption” of this “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) because he specifically referenced it in Emergency Order #1 on March 15, three days before the public learned of it.

- This uncomfortable fact also suggests Governor Sununu knew of its purported “adoption” much earlier because, without this amendment, Emergency Order #1 and its directive to implement remote instruction for more than five days would not have been possible.

- The “emergency” amendment to ED 306.18(a)(7) was eventually made permanent. There no longer exists any limit on remote instruction in New Hampshire public schools.

The fact that two high-level departments in the New Hampshire state government (the Governor’s office and DOE) fundamentally altered the way in which school districts educate children – literally overnight without a hint of explanation or notice to the public – poses serious questions about transparency and whether the rule of law still existed during this feigned and prolonged “public health emergency.”

Apart from the government’s lack of transparency and accountability, this illegal rule change impacted thousands of children. Although remote learning sounds wonderful in theory, leaving children alone to engage in self-directed electronic learning is grossly inadequate to meet the educational needs of New Hampshire children, and the requirements of the New Hampshire Constitution and applicable statutes and rules. Children require guidance and social interaction. These measures (along with school district mask mandates) negatively impacted children state-wide, and its long-term effects have yet to be fully determined.

As remaining COVID-19 measures disappear, many people are drawing comfort from the possibility that this “pandemic” is drawing to a close. While that may be true, we need to continue to take note of what we lost throughout this two-year ordeal and learn how to prevent our federal, state, and local governments from implementing these measures again in the future. As noted above, there no longer is any restriction on remote learning in New Hampshire — because our state government changed those requirements overnight under the guise of public safety. This change permits them to do it again and will impact our children for a long time.