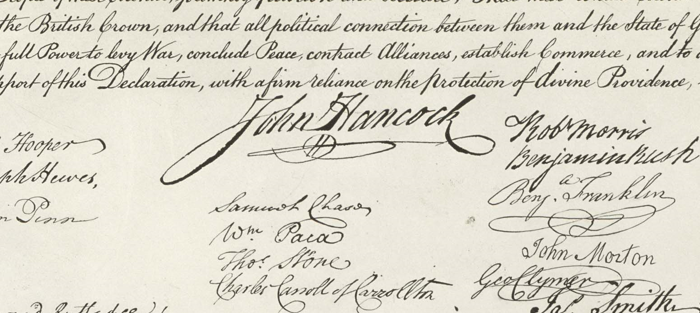

On July 6, 1776, John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, wrote to the Committee of Safety at Exeter, N.H. to inform them that Congress had declared independence from Great Britain. (Here’s a copy of his letter to Georgia).

In his letter to George Washington, written the same day, Hancock remarked on the heavy responsibility of governing.

“Altho it is not possible to foresee the Consequences of Human Actions, yet it is nevertheless a Duty we owe ourselves and Posterity, in all our public Counsels, to decide in the best Manner we are able, and to leave the Event to that Being who controuls both Causes and Events to bring about his own Determinations.”

The 39-year-old Hancock shared wisdom that has escaped many who enjoy elected service at much older ages. Our actions have consequences we can’t foresee— because humans empowered with free will desire to determine their own fate. They are not a breed for following instructions with docile servility.

We want to thank Drew Cline for this Op-Ed. If you have an Op-Ed or LTE

you would like us to consider, please submit it to Editor@GraniteGrok.com.

This concept of unintended consequences was spreading rapidly through the world in 1776. Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, published that year, addressed it most famously with the “invisible hand” metaphor. “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from regard to their own self interest.”

John Locke had warned of the unintended consequences of well-intentioned legislation in the 1690s.

Ideas like these were awakening minds in the 1760s and 1770s. The pubs, taverns, inns and coffee houses of Britain and its colonies, conversations were fired with revolutionary ideas such as this. The rights of man; individual liberties; the boundaries of government power; the right to self-rule.

In the colonies, the awesome responsibility of self-government was borne not by aristocrats and royals, but by farmers and shop keepers. They were learning, as Hancock said, “to decide in the best manner we are able” their own affairs, their own fates. And in so deciding, they were seeing that their actions produced results both intended and unintended. That insight inspired them (not always, but often) to be cautious in their governing, to recognize that they lacked the knowledge and wisdom to decide others’ affairs for them.

In the 245 years that followed that momentous year, most of the former North American colonies slowly let those Enlightenment ideals slip away.

One did not.

The spirit of ’76 lives most strongly in New Hampshire, whose state motto has helped to preserve a culture of independence and individualism. This culture has led to the remarkable passage of two state budgets this century that have lowered state spending and taxes. The budget that took effect last week made New Hampshire the only Northeastern state to have no tax on individual income.

The policies produced by this culture haven’t gone unnoticed among our neighbors. Some of them are urging their states to become more like ours.

Maine Policy Institute President Matthew Gagnon last week wrote an essay pointing out how much freer New Hampshire is than its neighbor to the East. He summarizes the different governing paths these adjoining states have taken and illustrates the unintended consequences of Maine embracing bigger government decades ago.

We share this essay below as a reminder that the failure to choose freedom has lasting negative consequences, as Hancock and company understood.

A culture of freedom is lost if not consciously cultivated. New Hampshire has preserved a uniquely freedom-loving culture for two-and-a-half centuries. But it can be lost here, too, if we stop cherishing and nurturing it.

New Hampshire: the way government ought to be

The following essay by Matthew Gagnon, president of the Maine Policy Institute, was first published in the Bangor Daily News. It is reprinted with permission from the Maine Policy Institute.

New Hampshire and Maine are both states in northern New England, and are very similar in many ways. They are both rural in character, with populations of around 1.3 million people, and both are filled with rugged, hard-working people with a distinct culture.

Yet for all their similarities, Maine and New Hampshire are also different in many ways, most notably in the political culture that has developed in each.

Never has that been on display more than in the period of time surrounding the pandemic, as Gov. Chris Sununu and Gov. Janet Mills — and their respective Legislatures — have pursued very different approaches to managing the public health challenge presented by COVID-19. Generally speaking, Sununu and New Hampshire lawmakers favored a lighter touch — and seemed slower to institute restrictions — while insisting on the participation and collaboration of the elected legislature, which returned to work last June.

Maine’s instinct, by contrast, seemed to be far more cautious and restrictive on everything from mask wearing, to crowd size limitations and travel restrictions. And, of course, Maine lawmakers adjourned last March for nearly the whole year, content to allow Mills to run the state via emergency powers.

Those different reactions ultimately stem from the very different philosophies of the people of each state. That observation, by the way, is a reasonably non-partisan one. Even Democrats in New Hampshire have historically defended a far more hands-off approach to governance and taxation, and favored more restraint on spending issues.

But where does this difference come from? For my part, I look back to the early 1970s.

In 1971, Maine considered a referendum that asked citizens whether or not they wanted to repeal the income tax, which had been created at the behest of Gov. Ken Curtis in 1969. In the end, voters chose to reject the attempt to repeal it.

In New Hampshire, by contrast, something interesting happened in 1972. That year a little-known politician named Meldrim Thomson was attempting to win a race for New Hampshire governor, and was seeking a way to stand out from the crowd. He decided to try a new approach, making his primary message one of antipathy toward taxes, coining the term “ax the tax” and asking candidates for office to join him in taking a pledge to “practice economy and frugality.”

At the time, there were many calling for New Hampshire to adopt an income tax, as Maine had, to raise more revenue for the state and provide more services to citizens. Unlike Maine, however, the anti-tax message caught on and Thomson was able to defeat the incumbent Republican Gov. Walter Peterson in a primary, and then win the governorship that November.

To observers, it is quite clear that after this point, the divergent philosophies ended up producing two radically different political climates.

As New Hampshire grew more economically prosperous, politicians and voters in the Granite State came to see the difference in their state as “The New Hampshire Advantage,” and fiercely defended their approach as a selling point for economic development in their state.

This month, though, the differences between the two states grew even more stark as each moved toward passing their respective state budgets.

In Maine, spending continues to grow, while in New Hampshire they have actually cut — yes cut — General and Education Trust Fund spending by $172.5 million. New Hampshire also eliminated the tax on interest and dividends, which actually makes the state completely income tax free for the first time. They also cut business tax rates and cut the statewide property tax. In addition New Hampshire pursued major reforms, such as the creation of Education Savings Accounts, which will radically increase choice in education for students and parents.

But most amazingly of all, inside the new New Hampshire budget, lawmakers agreed to language that would grant the state Legislature more authority during states of emergency. Despite the fact that the state — like Maine — is controlled entirely by one party, legislators have now limited the governor’s powers, requiring a session of the Legislature be called after 90 days of an official state of emergency. Once in session, it would be up to lawmakers, not the governor, to uphold or end the emergency declaration.

Maine prides itself on its motto, “the way life should be.” I have a suggestion, though, for our neighbors in New Hampshire. Consider a new motto of your own: “The way government should be.”