The Declaration of Independence asks and answers two fundamental questions about the nature of government, as understood by the people who founded America. First, what is government for? Second, from where does government derive its just powers?

Those are the questions. The answers? Men form governments to protect their rights — which must necessarily be rights they already have. And governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.

So that’s the theory on which the country was founded. But the practice of government in this country has drifted about 180 degrees away from the theory. And I believe much of this drift has been made possible by allowing ourselves to ignore that critical word: consent.

Recently I was talking to a friend who was about to head off to college. I mentioned that in political discussions, you almost never hear anyone ask those two questions I referred to earlier. She surprised me by saying that they had been raised in her civics class. (She graduated this year from the Academy for Science and Design in Nashua.)

So I asked her what answers the class had come up with. She said that they were told that the purpose of government was to ‘do things that people need to have done’, and that government gets its power from ‘majority rule’. (Interestingly, her senior project was an analysis of some of the ways in which various voting methods fail to properly represent the views of the majority.)

Of course, within about two minutes, she was able to see that majority rule couldn’t be the source of power, or else there would be no such thing as rights, which would obviate the need for a Bill of Rights. And it would make a constitution irrelevant as well, since a majority that is the source of power can do whatever it wants, whenever it wants.

Apparently there wasn’t time to let the students consider other views. And this is at one of the #leastworst schools in the state, maybe in the entire country! That’s something to think about the next time you find yourself saying that ‘we need to teach the constitution in schools’.

So what, exactly, is the difference between government by consent and government by majority rule? We can put them into pretty clear contrast by asking this question: If some other people want to take one of your kidneys, and you don’t want them to, how many of them would it take to outvote you? To ask that a different way, how many other people does it take to provide consent for you?

There isn’t any number big enough, is there? Except in special cases (like a parent consenting for a child, or a guardian consenting for a ward), absent a power of attorney or equivalent document, no one can consent for anyone else.

This means that a government that derives its just powers from the consent of the governed has two choices: It can limit itself to the exercise of just powers, for which it obtains the consent of individuals; or it can expand into the exercise of unjust powers, for which it substitutes something else for that consent.

In the latter case, the question is: What is that something else? We often act as if it’s majority rule, but as I’ve noted, that can’t really be the case, unless there’s no such thing as rights. And as even Rachel Maddow admits: ‘The thing about rights is that they’re not actually supposed to be voted on. That’s why they’re called rights.’

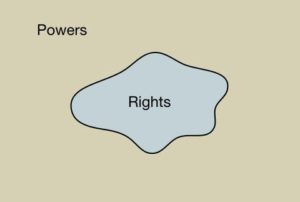

Now, while people may disagree about which rights exist, and to what extent they may be limited, nearly every American has some intuitive understanding of the basic idea that there are some areas of life that are, as Ms. Maddow notes, simply beyond the reach of any majority, no matter how large. In this view, government has the power to do pretty much anything, except in those areas that have been fenced off by being identified as rights:

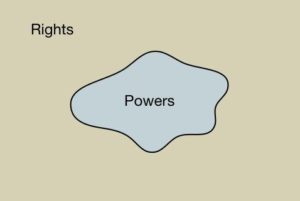

But if we take seriously the idea of consent, then the picture is exactly reversed: people start out with the right to do pretty much anything, except infringe on the rights of others; and to protect those rights, they consent to let government exercise certain powers on their behalf:

Let’s take a look at the Declaration of Independence again:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…

Which of those pictures better represents these ideas?

Now, it’s fair to ask: Does this matter? Is it just an academic distinction, a distinction without a difference?

I don’t think it is, and an example can help illustrate why. Suppose there is something I can legitimately hire someone to do, like paint my house, or plow my driveway, or watch my property while I’m away, or act as a bodyguard for me and my family. I’m delegating a power to that person, right? Which is another way of saying that I’m consenting to let him exercise that power.

Here are two important questions: (1) Does the fact that I’ve delegated that power mean that I can no longer exercise it myself? (2) Can I delegate that power on behalf of someone else, without his consent?

The answers, of course are: (1) No, and (2) Hell no.

To use the terminology of the New Hampshire constitution, when I delegate a power to someone, that person becomes my substitute or agent. It’s absurd to imagine that my substitute or agent can have more power than me. It’s also absurd to imagine that I can designate someone to be your substitute or agent.

But that’s exactly how we treat consent and delegation when it comes to government!

That is, we imagine that it makes sense to think that if I delegate to government the power to coin money, or organize post offices, or arrest criminals, or defend me and my property, or hand out certificates of competence, I give up the power to do those things myself. This is confusing a delegated power with a monopoly.

Worse, we imagine that it makes sense to think that if enough of us feel like delegating a power to someone, we can delegate that power on behalf of people who don’t want us to. This is confusing consent with majority rule.

This kind of confusion — pretending that we’re doing one thing, when we’re really doing something completely different — is like setting out to sea with a compass that consistently points in the wrong direction. If you’ve ever found yourself wondering how we, as a country, have allowed ourselves to drift so far off course… well, this is how.