The protections in the original Bill of Rights applied only to the federal government. So, the federal government couldn’t set up an official religion, or punish you for saying something, or disarm you, or search your home without a warrant, and so on. But the states could do those things.

An essential goal of the 14th Amendment was to extend those protections to the state level. But a few years after its ratification, the Supreme Court effectively repealed that part of the Amendment, ruling that the phrase ‘privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States’ applied only to things like voting in federal elections, or traveling on interstate waterways, and not to things like freedom of speech, keeping and bearing arms, and so on.

Decades later, the Court decided that perhaps the states should have to respect some aspects of some rights mentioned in the Bill of Rights. This was a problem, because it had previously killed the Privileges and Immunities clause of the 14th Amendment.

But it hadn’t yet killed the Amendment’s guarantee of ‘due process of law’ to everyone. So the Court invented the oxymoronic term ‘substantive due process’, and said that some rights were protected, not because they were actual rights, but because their exercise was part of substantive due process, which — since it had the words ‘due process’ in its name — was still guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

So what does that mean, exactly? Well, as far as anyone can tell, something is part of substantive due process if it is ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty’.

But what does that mean? Roughly, the Court asks: Is the ability to [fill in the blank] part of what we mean by living in a ‘free country’? If the answer is yes, then it’s part of substantive due process. And if the answer is no, then it’s not.

To illustrate: Let’s say you think the 2nd Amendment protects your right to own a semi-automatic rifle. If the Court believes that the ability to own one is implicit in the concept of ordered liberty, then that’s part of substantive due process, and you can own it. But if the Court believes that it isn’t, then it’s not, and you can’t.

So, in case you were wondering why only some kinds of arms seem to be protected by the 2nd Amendment, and why only some kinds of speech seem to be protected by the 1st Amendment, and why only some kinds of warrantless searches seem to be forbidden by the 4th Amendment, and so on… well, this is why. Substantive due process is a kind of legal strainer — you shove a right through it, and the parts that the Court likes get through, and the parts that the Court doesn’t like get discarded.

In that sense, the 14th Amendment, which was supposed to bolster the Bill of Rights, ended up more or less destroying it.

Now let’s fast forward to 2012. In that year, speaking for the Obama administration, Attorney General Eric Holder made the startling claim that

a careful and thorough executive branch review of the facts in a case amounts to ‘due process’ and that the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment protection against depriving a citizen of his or her life without due process of law does not mandate a ‘judicial process.’

No catchy name was invented for this idea, so we can just call it ‘executive due process’.

Note that he didn’t say that any particular person in the executive branch — like the President, or the governor of a state — had to do this review. It could be done by any bureaucrat, or agent, or officer.

And while he was talking specifically about depriving a citizen of life, it seems clear that once your right to life is to be viewed through the lens of executive due process, all your other rights will be viewed through the same lens.

Which brings us to the latest step in the devolution of due process. Recently, in support of Red Flag laws, President Trump coined a new term: ‘rapid due process’. It’s an attractive term, in that it suggests that the normal protections will remain in place, but the process of observing them will move a little faster. That’s a good thing, right?

But the name is intentionally misleading. What he actually means is something like ‘pre-emptive due process’. As he put it during one press conference: ‘Take the guns first, go through due process second.’

Again, he’s talking specifically about guns here, but there’s no reason to expect that rapid due process won’t become the norm for dealing with rights of all kinds. And from his perspective, the beauty part is that the executive doesn’t even have to ask the judiciary to approve its decisions, thanks to the doctrine of executive due process. (What, you want a judge involved? That’s sooooooooooo 2011. We’ve moved on. Get over it.)

The history of due process is the history of the destruction of individual rights in America.

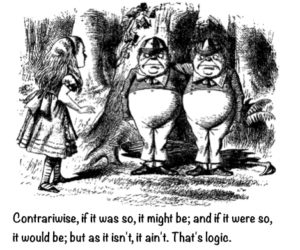

That is, we started out with a bunch of rights. Those were replaced with a single right to substantive due process, where judges decided which parts of which rights were implicit in the concept of ordered liberty. Then executive due process removed judges from the picture, leaving those decisions up to the executive branch. And now we have rapid due process, in which time has been eliminated as a constraint — as the Red Queen might put it, ‘Sentence first, verdict afterwards’.

What will the next step be? Well, now that time is no longer a factor, I can’t help thinking that it will have something to do with reparations, and a new concept called ‘overdue process’.

You heard it here first.