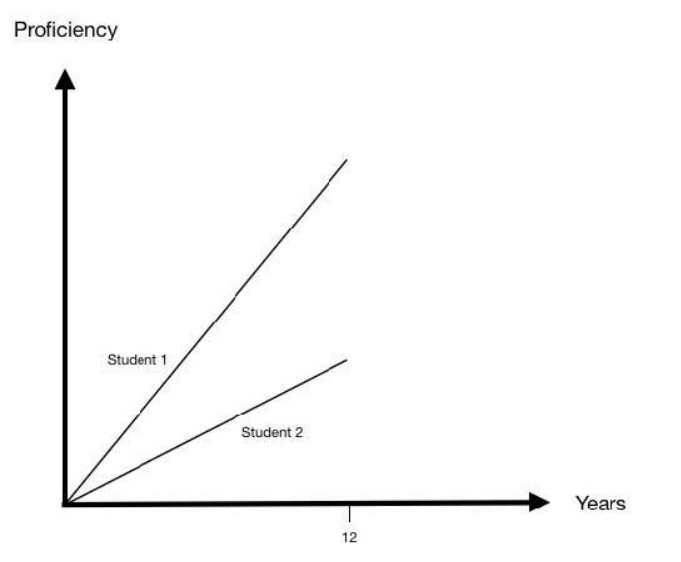

Below is a picture of the current educational system. We put kids in school for about 1000 hours per year, for 12 years, and see what happens. At the end of that time, some may be taking college-level courses. Others may still be unable to read.

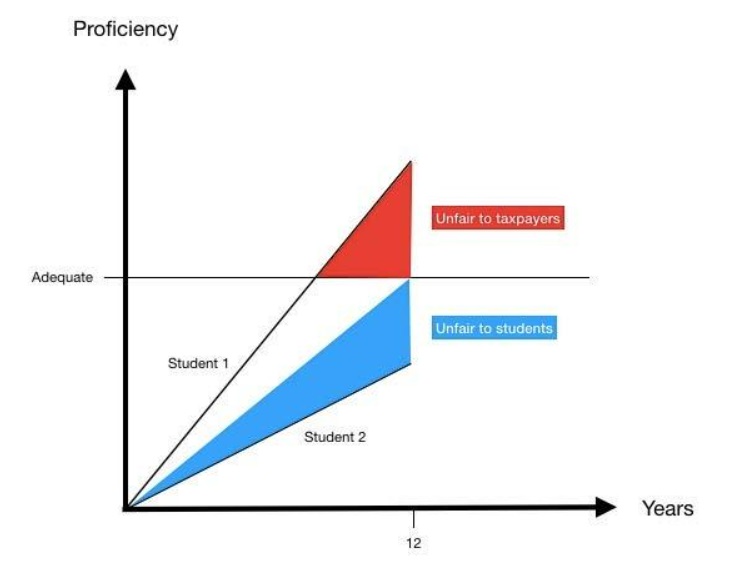

This approach is unfair to at least two important groups of people.

- Students who are pushed out of the system before they’ve reached the proficiency required to justify the very existence of the system.

- Taxpayers who end up supporting abler students for longer than necessary, paying for courses that exceed an ‘adequate education’.

But both types of unfairness can be eliminated — and a ton of money saved — with a couple of fundamental changes to the way we think about why we’re doing all this in the first place.

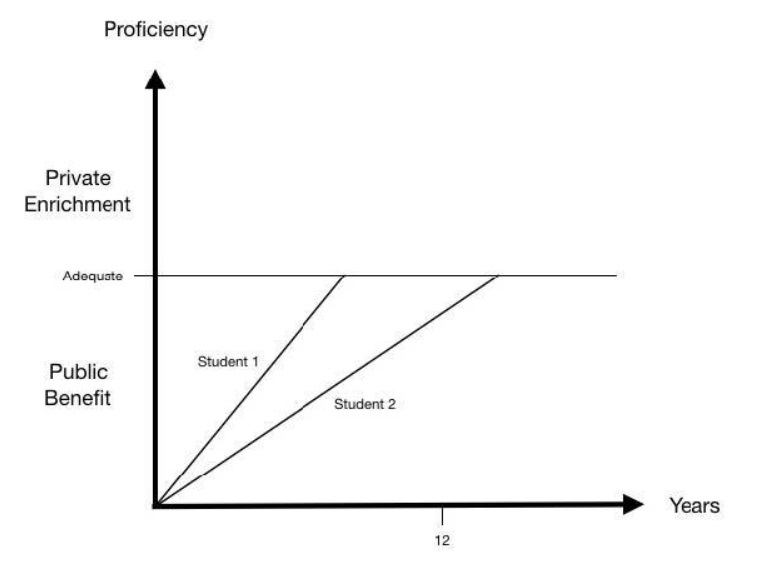

- If the point is for kids to be educated, then we should use some standard level of achievement, rather than age or time in class, to decide when students are ready to leave school (and when taxpayers can stop subsidizing them).

- If the point of using taxes is that we all benefit from an educated populace, then we should use those taxes to subsidize only subjects that provide a clear public benefit (literacy, numeracy, logic, scientific reasoning) as opposed to private enrichment (advanced placement or college courses, preparation for specific jobs, arts, sports).

What it comes down to is this: As a taxpayer, I derive considerable benefit from not being surrounded by people who are illiterate, innumerate, or irrational. So it makes sense for me to pay to prevent that.

On the other hand, I derive no benefit at all from being surrounded by people who can speak a few words of Spanish, or play the trombone, or hit a fastball, or identify some of the characters in one or two of Shakespeare’s plays. So I shouldn’t be paying for any of those things.

What about things like AP Calculus? Well, consider that if a student can already read and write and understand algebra, he doesn’t really need his town to spend a few thousand dollars so he can have a teacher read his textbook to him. Apart from just learning it the old-fashioned way (read chapter, work exercises, repeat), the Internet is brimming with people and companies who are eager to teach him AP Calculus (or anything else) for next to nothing, and often for free.

What about things like vocational training? Well, do we ask towns to pay for law or medical or dental school? For IT certification? For courses in massage therapy, or acupuncture, or flower arrangement, or aviation, or cooking? We don’t. Towns should be paying to get students to the point where they can succeed at job training. That’s a public benefit. Providing (or paying for) the training itself is private enrichment.

Naturally, there’ would be a lot of lobbying by parents to include particular subjects under the umbrella of ‘adequate education’, in order to use other people’s money to enrich the lives of their own children. (And similar lobbying by teachers, to enrich themselves.) But I think we can short-circuit a lot of it by adopting two pretty simple rules:

- If there is significant controversy about whether something should be taught, then it is by definition political in nature, and its teaching should not be funded with taxes.

- If something isn’t essential enough to be mandatory, it’s not essential enough for its teaching to be funded by taxes.

Forget about children being ‘left behind’. If we give up the astrological model of education (i.e., that we can tell what a child should be learning at the moment by checking his date of birth), then being left behind isn’t even a sensible concept. Each kid gets the same education, which takes as long as he needs. What could be fairer than that?

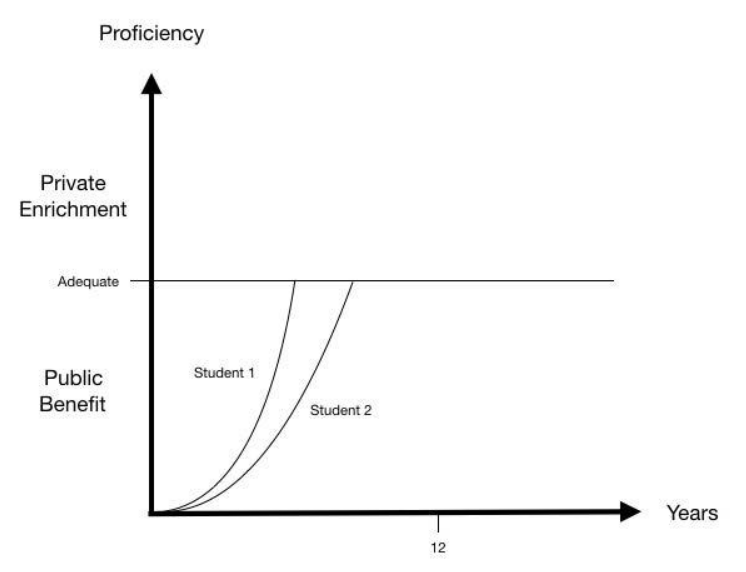

Forget about trying to force a ‘uniform property tax rate’, or looking for new sources of revenue to keep propping up a failing system. If we teach kids what they need to learn in order to keep teaching themselves, and let them take it from there, it should cost a tiny fraction of what we’re spending now. That is, that final picture should really look more like this:

Every town should be able to afford it with relative ease, compared to what they’re spending now. What could be fairer than that?

If we want fairness in education — fairness to the benefactors as well as the beneficiaries — and if want to avoid bankrupting ourselves trying to provide it, we need to start by reconsidering what fairness actually means. Like perfection, fairness is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.