For the last several months, many of us have been waiting on pins and needles for a judge to tell us what the state constitution says about education, which is remarkable because it’s not like that constitution is written using particularly difficult language.

How many of us would have trouble understanding a sentence like this?

Free and fair competition in the trades and industries is an inherent and essential right of the people and should be protected against all monopolies and conspiracies which tend to hinder or destroy it.

Do we need a judge to tell us that a public school monopoly in the industry of education is something from which the people are to be protected?

Would we have trouble understanding this sentence?

[I]t shall be the duty of the legislators and magistrates, in all future periods of this government, to cherish the interest of literature and the sciences, and all seminaries and public schools

Do we need a judge to tell us that, whatever ‘cherish’ may mean, it can’t sensibly mean one thing for seminaries (which can’t be funded, operated, or regulated by the state) and something completely different for public schools?

We don’t. Or we shouldn’t. But people seem to have lost all confidence in their ability to read simple declarative sentences, and determine what they mean.

How does something like this happen?

Here’s one clue. We currently have a public school system in which less than half of students can read or do math proficiently. (And in case you’re thinking this is a recent development, it’s been true since at least the 1970s, when we started collecting NAEP data.) Which means that the system operates largely by having the students sit passively while their teachers ‘explain’ what is in their textbooks.

In other words, the teachers read the books — or at least, the teachers’ guides to the books — and relay that information to the students. The students have no idea whether that information is being relayed accurately, and no idea that they could check that for themselves by reading the books. So they have very little choice but to just accept what they’re told.

That’s a hell of a lot of power to put in the hands of teachers — who are, we should never for a moment forget, employees of the state.

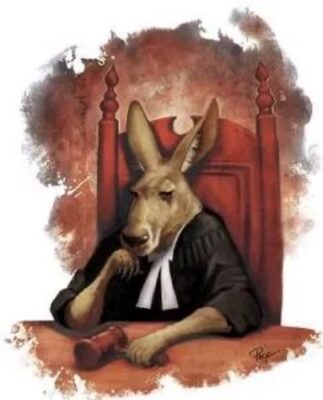

Isn’t that how we treat our constitution, and our courts? The judges work from the opinions of other judges, instead of from teachers’ guides. But otherwise, it’s pretty much the same.

That’s a hell of a lot of power to put in the hands of judges — who are, we should never for a moment forget, employees of the state.

In 1927, General John McAuley Palmer said that professional armies

threaten government by the people, not because they consciously seek to pervert liberty, but because they relieve the people themselves of the duty of self-defense. A people accustomed to let a special class defend them must sooner or later become unfit for liberty.

I believe the same thing is true of ‘professional readers’, including judges and teachers. By relieving us of the duty of understanding things for ourselves — and by abusing the power that they gain by doing this — they have made us unfit for liberty.

What can we do about that? A good first step would be to elect legislators who would be willing to say to the courts:

You are not the boss of us. We can read the constitution as well as you can. And we’re no longer going to let you get away with pissing on our legs and telling us that it’s raining.

And a good second step would be to become people who are willing to say the same thing to those legislators.