The federal court system has three main levels: district courts (the trial court), circuit courts which are the first level of appeal, and the Supreme Court of the United States (“SCOTUS”), the final level of appeal in the federal system.

Only the SCOTUS is specifically established in Article III of the Constitution. The Courts of Appeal and the District Courts are established under Congressional legislation enabled by Article III of the Constitution.

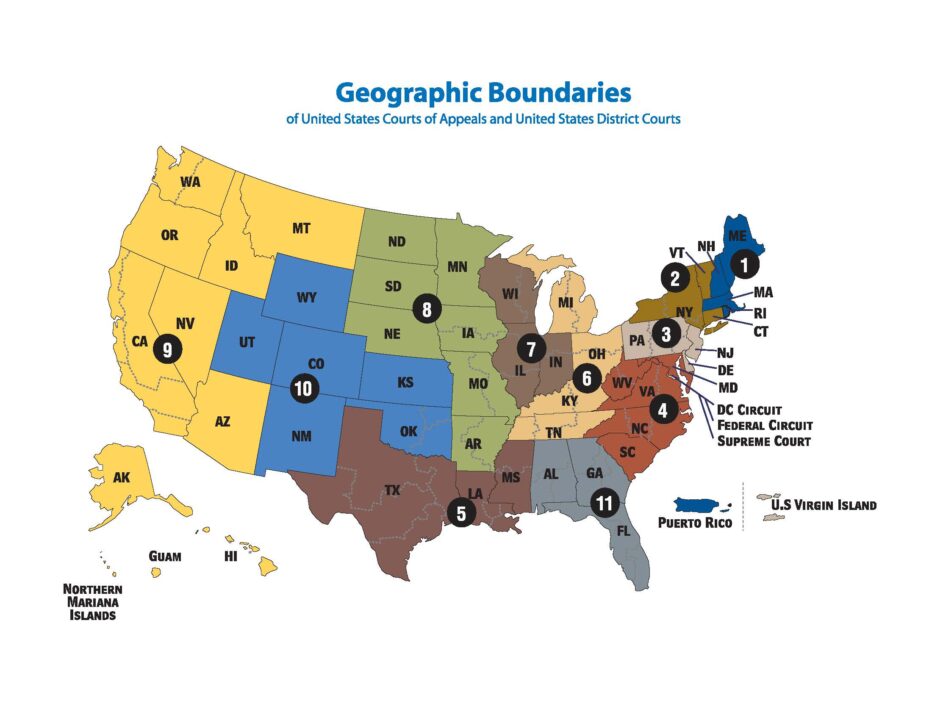

There are 94 district courts, 13 circuit courts, and one Supreme Court throughout the country.

Courts in the federal system work differently in many ways than state courts. The primary difference for civil cases (as opposed to criminal cases) is the types of cases that can be heard in the federal system.

Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction, meaning they can only hear cases authorized by the United States Constitution or federal statutes.

The federal district court is the starting point for any case arising under federal statutes, the Constitution, or treaties. This type of jurisdiction is called “original jurisdiction.” Sometimes, the jurisdiction of state courts will overlap with that of federal courts, meaning that some cases can be brought in both courts. The plaintiff has the initial choice of bringing the case in state or federal court. However, if the plaintiff chooses state court, the defendant may sometimes choose to “remove” the case to federal court. Some commentators have suggested that removal of a case to federal court from state court might ameliorate or eliminate any “home court” advantage that notionally might exist in a state court proceeding

Cases that are entirely based on state law may be brought in federal court only under the court’s “diversity jurisdiction.” Diversity jurisdiction allows a plaintiff of one state to file a lawsuit in federal court when the defendant is located in a different state. The defendant can also seek to “remove” a case from state court to a federal court. To bring a state law claim in federal court, all of the plaintiffs must be located in different states than all of the defendants, and the “amount in controversy” must be more than $75,000. (Note: the rules for diversity jurisdiction are much more complicated than explained here.)

Criminal cases may not be brought under diversity jurisdiction. States may only bring criminal prosecutions in state courts, and the federal government may only bring criminal prosecutions in federal court.

Also important to note is that the principle of double jeopardy (embodied in the Fifth Amendment to the US Constitution) – which does not allow a defendant to be tried twice for the same charge – does not apply between the federal and state government, which are considered to be different “sovereigns.” If, for example, the state brings a murder charge and does not get a conviction, it is possible for the federal government in some cases to file charges against the defendant if the act is also illegal under federal law.

Federal judges (and Supreme Court “justices”) are selected by the President and confirmed “with the advice and consent” of the Senate and “shall hold their Offices during good Behavior.” Judges may hold their position for the rest of their lives, but many resign or retire earlier or may choose to take “senior” status in which they undertake to adjudicate only a limited number of such cases as they wish to handle. They may also be removed by impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate. Throughout history, fourteen federal judges have been impeached and removed due to alleged wrongdoing; and one Supreme Court Justice was impeached by the House but not convicted or removed by the Senate.

District Courts: The district courts are the general trial courts of the federal court system. Each district court has at least one United States District Judge, appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate for a life term. District courts handle trials within the federal court system – both civil and criminal. A District Judge is are able to continue to serve so long as he or she maintains “good behavior,” and they can be impeached and removed by Congress.

Each state has at least one district court, and more populous states are typically divided into multiple districts within the state. There are over 670 district court judges nationwide.

Some tasks of the district court are delegated to federal magistrate judges. Magistrate judges are appointed by the district court by a majority vote of the judges and serve for a term of eight years if full-time and four years if part-time, but they can be reappointed after completion of their term. In criminal matters, magistrate judges may oversee certain cases, issue search warrants and arrest warrants, conduct initial hearings, set bail, decide certain motions (such as a motion to suppress evidence), and other similar actions. In civil cases, magistrates often handle a variety of issues such as pretrial motions and discovery issues.

An exception to lifetime appointment is for magistrate judges, who are selected by district judges and serve a specified term. They were formerly called simply federal “magistrates,” and are generally not considered to be Article III judges with lifetime tenure. Their decisions and “findings” can be appealed to the District Court.

Federal trial courts have also been established for a few subject-specific areas. Each federal district also has a Bankruptcy Court for those proceedings.

Another exception to lifetime appointment is for Bankruptcy Judges, who are selected by the majority of judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals to which his or her specific district court is attached and serve a specified term. Bankruptcy Judges exercise jurisdiction over bankruptcy matters and their decisions can be appealed to the District Court. Bankruptcy Judges were formerly called “referees in bankruptcy” and are generally not considered to be Article III judges with lifetime tenure.

There are some additional specialized federal courts with nationwide jurisdiction for issues such as tax (United States Tax Court), claims against the federal government (United States Court of Federal Claims), and international trade (United States Court of International Trade).

Courts of Appeal: Once the federal district court has decided a case, the case can be appealed to a United States Court of Appeal. There are twelve federal circuits that divide the country into different regions. The Fifth Circuit, for example, includes the states of Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Cases from the district courts of those states are appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which is headquartered in New Orleans, Louisiana. Additionally, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals has a nationwide jurisdiction over very specific issues such as patents.

Each Circuit Court of Appeal has multiple judges, ranging from six on the First Circuit to twenty-nine on the Ninth Circuit. Circuit court judges are appointed for life by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

Any case may be appealed to the circuit court once the district court has finalized a decision (some issues can be appealed before a final decision by making an “interlocutory appeal”). Appeals to circuit courts are first heard by a panel, consisting of three circuit court judges. Parties file “briefs” to the court, arguing why the trial court’s decision should be “affirmed” or “reversed.” After the briefs are filed, the court may schedule “oral argument” in which the lawyers come before the court to make their arguments and answer the judges’ questions.

Though it is rare, the entire circuit court may consider certain appeals in a process called an “en banc hearing.” (The Ninth Circuit has a different process for en banc than the rest of the circuits.) En banc opinions tend to carry more weight and are usually decided only after a panel has first heard the case. Once a panel has ruled on an issue and “published” the opinion, no future panel can overrule the previous decision. The panel can, however, suggest that the circuit take up the case en banc to reconsider the first panel’s decision.

Beyond the Federal Circuit, a few courts have been established to deal with appeals on specific subjects such as veterans claims (United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims) and military matters (United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces).

Supreme Court of the United States (“SCOTUS”): The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the American judicial system and has the power to decide appeals on all cases brought in federal court or those brought in state court but dealing with federal law. For example, if a First Amendment freedom of speech case was decided by the highest court of a state (usually the state supreme court), the case could be appealed to the federal Supreme Court. However, if that same case were decided entirely on a state law similar to the First Amendment, the Supreme Court of the United States would not be able to consider the case.

After the federal circuit court of appeal or A state supreme court has ruled on a case, either party may choose to appeal to the Supreme Court. Unlike circuit court appeals, however, the Supreme Court is usually not required to hear the appeal. Parties may file a petition for a “writ of certiorari” to the court, asking it to hear the case. If the writ is granted, which is solely within the discretion of the Justices (at least 4 of whom must agree to a grant of the writ), the Supreme Court will take briefs and conduct oral argument. If the writ is not granted, the lower court’s opinion stands. Certiorari is not often granted; less than 1% of appeals to the high court are actually heard by it. The Court typically hears cases when there are conflicting decisions across the country on a particular issue or when there is an egregious error in a case.

The members of the SCOTUS are referred to as “justices” and, like other federal judges, they are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate for a life term. Although the Constitution does not set the number of Justices of the SCOTUS, Cogrressional legislation has set the number of Justices, which have varied over time, there are at present (and with that number having been in force for many years) nine justices on the court – eight associate justices and one chief justice.

The Constitution sets no formal requirements for Supreme Court justices, though all current members of the court are lawyers and most have served as circuit court judges. Justices are also often former law professors. The chief justice acts as the administrator of the court and is chosen by the President and approved by the Congress when the position is vacant.

The Supreme Court meets in Washington, D.C. The court conducts its annual term from the first Monday of October until each summer, usually ending in late June.

Next up: Nationwide injunctions issued by US District Court Judges; and more details about SCOTUS- tune in soon!