Confucius said that the first step towards wisdom is to call things by their right names. It’s a good rule to live by. If you misname something, you won’t really be able to think about it correctly, because you’ll be thinking about what it’s called, rather than about what it is. On the other hand, if you name something very accurately and precisely, many of the straw man arguments against it can’t gain any traction.

Let’s apply this reasoning to ESAs, or Education Savings Accounts, and see where it takes us.

The first thing to note about these accounts is that they aren’t savings accounts at all. The accounts don’t contain money that people have saved from their own incomes. The accounts contain money given to those people, after being taken from other people. They are spending accounts.

So it would be more accurate to call them Education Spending Accounts (ESAs). This would make it harder to confuse them with things like tax-deferred retirement accounts, or the 529 plans that people use to save for college.

Second, they’re not really about education per se. If they were, they would be universally available. But, at least as configured in New Hampshire, you have to qualify for an account by spending some minimum amount of time in public schools, to demonstrate that they aren’t a good fit for you. Then you can use an ESA to escape from the public school system.

So it would be more accurate to call them Public School Escape Spending Accounts, or more simply, Escape Spending Accounts (ESAs). This would make it harder to argue that they pose an existential threat to the public school system, by making it clear that they are targeted at a small number of kids who are not well-served by that system.

Third, although the name ‘account’ is accurate, it points to one of the major flaws of the program. That is, one of the selling points that is often brought up by proponents of ESAs is that if you don’t spend all the money in the account by graduation, you can use it for college.

But when did the state’s court-mandated responsibility to provide the opportunity for an adequate education expand to include paying for college? That clearly crosses the line between public benefit (which can be subsidized by taxes) and private enrichment (which cannot).

Fourth, there is the question of who should be getting this money. The bills that were submitted in the last session contained restrictions based on family income, and other considerations. But here we can take a lesson from the name of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, SNAP. ‘Assistance’ is clearly something we give to people who need it, and not to people who don’t need it.

So it would be more accurate to talk about the Escape Assistance Program, EAP. This would send a clear signal that these funds are not intended for people who have the money to educate their own children without help from the state.

Fifth, any program like this has to address the fundamental tension between freedom (for parents to do what they think is best for their kids) and accountability (to the taxpayers who are footing the bill). If you’re taking my money, I need to know that you’re not wasting it.

There are two ways to waste that money, which have to be dealt with separately.

The first way to waste the money is to spend it on low-quality goods and services (e.g., ‘Joe Bob’s Math Shack’). The second is to spend it on private enrichment (e.g., AP courses, music lessons, welding classes), rather than on things that provide a clear public benefit.

The way we normally deal with the first consideration, at least in schools, is through credentialing. Teachers and administrators get licenses, and schools get accreditation, and it all adds up to a kind of promise: If you send us your kids, you can trust us to educate them.

Of course, the problem with this kind of credentialing is that is doesn’t really work very well. As evidence of that, consider that our current graduation rate is above 90%, while the number of students who have reached proficiency (as measured by the NAEP exam and other standardized assessments) by graduation is around 40%.

In the real world, we deal with this in a much more straightforward way: You withhold payment until the job is done. You don’t give your mechanic money up front, and then hope that he does a good job. You don’t pay for your meal, and then hope that the food and service are acceptable. Everywhere outside of education, the work gets done, or the goods get delivered, and only then does payment change hands.

The way we normally deal with the second consideration is to set up restricted payment pathways. For example, if you’re getting help with heating oil, or rent, or medical care, there’s no way for you to spend that money on anything else.

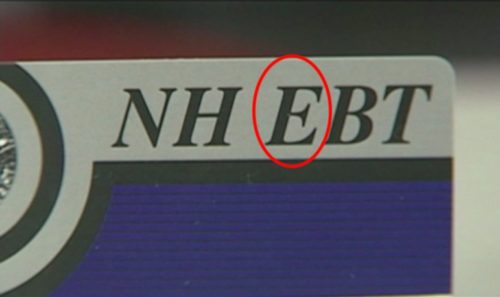

Interestingly, the EBT system for distributing SNAP funds addresses both of these considerations at once: Your card doesn’t get charged until you have the food, and you can only spend the funds in certain kinds of establishments, for certain kinds of products.

There’s no good reason not to just fold the EAP framework into the existing EBT system. As with SNAP purchases, you would be able to make EAP purchases of a restricted set of educational goods and services, from a restricted set of educational establishments.

Now, to bring this in line with the way the rest of the world works, and to avoid the problems of meaningless credentialing, instead of requiring providers of educational services to get licenses or credentials from the state, we would simply pay only those providers who are able to demonstrate that they have provided an actual benefit.

For example, suppose you want to use your EBT card to pay a math tutor. Instead of requiring the tutor to get any particular kind of certification, you’d have to show — using a pre-test and a post-test — that he was actually able to teach you something! He does the work, and then he gets paid — reimbursed, if you will. And if he gets the job done, we don’t really care what licenses or certificates or other pieces of paper he has hanging on his wall.

Which brings us to our final name change: Escape Assistance Reimbursement Program, EARP, modeled after the SNAP and EBT programs.

Now, if a program with that name were implemented in a way that accurately reflected the name, who could argue against it? And how could the system be gamed, or abused?

It really does matter what we call things.