Mark Twain is supposed to have said, “Never argue with an idiot, they will only drag you down to their level and beat you with experience.”

That’s how I feel about the New Hampshire Supreme Court’s decision on the ConVal case (and the Claremont cases, for that matter). Their reasoning is hard to follow, but when you get down to it, they focus on irrelevant details. They’re not addressing the bigger picture.

Some very smart people get sucked into the details. In the process, they miss the forest for the trees.

Judges must thrive on this because they get to redefine words and ignore the actual text of the constitution in favor of prior decisions of the court, and whatever else floats their boat.

The Decision

The Contoocook Valley School District (ConVal), along with 19 other school districts, sued the state. They argued that the base amount ($4,100) that the state pays in adequacy grants to local school districts is unconstitutional because it’s far below what’s needed to provide an adequate education.

ConVal won in Superior Court. The state appealed it to the New Hampshire Supreme Court.

Last month, the Supreme Court agreed that the base amount needs to be increased to $7,356.01 per student. They also said that the courts couldn’t order the legislature to do it because of the separation of powers. But they did say that the legislature needs to change the law to reflect this increased amount.

That’s the decision.

Discussion

Many people have talked about the constitutional obligation of the state (Volinsky), whether the text of the constitution actually supports the decision (Cline), and the separation of powers (Lehman et al.). So I will not make those arguments here. But they do make for interesting reading and listening.

What do I think about the decision? So many things.

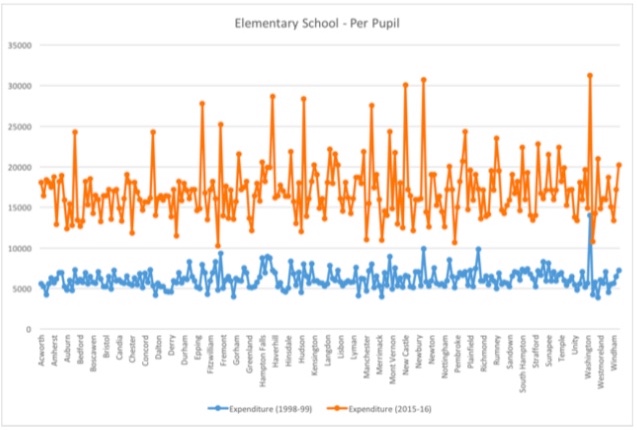

First, after the Claremont decision in 1998, school districts treated the state adequacy grants as extra money. We might more accurately call them “added-quacy grants.” Districts went from spending an average of $5,000 per pupil in 1998 to spending over $15,000 per pupil in 2015 (adjusted for inflation). Every school started spending as if they were a rich district.

And school spending continues to rise with no end in sight. I talked about that in a recent post, including a chart that shows the progression of actual spending from 2001 through 2024.

I fear that if the legislature increases the base adequacy amount, school spending will rise even more, which will increase our already out-of-control property taxes.

Second, there’s the amount. $7,356.01 per student is a lot less than the $27,000 we currently pay per student in New Hampshire. It seems very odd that the court could come up with such a precise number. But let’s assume for a moment that the courts can figure out how much is needed to provide an adequate education.

If that base adequacy amount is enough to provide an adequate education for students, and we already pay two to three times more than that, then why are less than 50% of NH students reading at a proficient level? Clearly no one — not the courts, and not the schools — has any idea how to provide an adequate education, let alone determine how much it costs.

Trying to put a price tag on something no one knows how to do is ridiculous.

Third, I wonder whether the legislature will enact the increased amount. This year, a provision of the budget stated that the court is not the legislature’s boss:

[T]he legislature now deems it necessary to definitively proclaim that, as the sole branch of government constitutionally competent to establish state policy and to raise and appropriate public funds to carry out such policy, the legislature shall make the final determination of what the state’s educational policies shall be and of the funding needed to carry out such policies.

HB2 2025

It could be that the court has just played into the hands of a legislature that actually wants to fix education. The legislature now has an opportunity to say that the court is misguided while they focus on the bigger problem.

Here’s what the legislature can do: Redefine an adequate education to have all students reading and doing math at proficiency by the 4th grade, and to maintain proficient reading and math levels until they graduate from high school.

When schools demonstrate that they can do that, we can start talking about how much an adequate education costs. And only then can we talk about what else might be part of an adequate education. Who knows? Maybe we’ll find out that it costs a lot less to provide an adequate education.

Think about it. It’s hard to imagine a reasonable definition of an adequate education that doesn’t include literacy and numeracy. Until recently, there was a law that said, all students must pass the state test — reading and math — at a proficient level. The schools ignored it. And one New Hampshire principal admitted that they don’t know how to teach reading. Teaching reading to all students is a problem that needs to be solved. And the law needs to include incentives to schools and to students to support this goal. Otherwise, they can just ignore the law again.

Once students know how to read proficiently, they can teach themselves anything they want.

That’s the bigger picture. It’s for the children.

In the meantime, if you’re not happy with your public school, you should take your children out. EdOpt.org can help you figure out what your next steps are.

Also, call or otherwise get a hold of your legislators to tell them this is a once in a lifetime opportunity. Please don’t blow it.