In prior installments of this series, state and national standardized test scores in New Hampshire and Vermont contradict the current narrative that the COVID pandemic shutdown caused children to suffer “learning loss.” Instead, the data reveals that the test scores have been deplorable for more than two decades and that they were in decline well in advance of the pandemic shutdown.

As elementary schools are tasked with teaching children how to read, we’ve looked at several in our region to assess both their scores and how they teach reading. Our reports on the Croydon Village School and Killington Elementary School reveal that there’s little, if any, evidence of “pandemic learning loss.” The Washington Elementary School seems to have been negatively affected by the pandemic shutdown. We were unable to determine whether or not the Albert Bridge School in Windsor was affected as Vermont won’t report its school-specific scores due to the school’s small size.

We now look at the Grantham Village School (GVS) in Grantham, NH.

Sydney Leggett has been the superintendent of the Grantham School District for six years. GVS houses Pre-K through grade 6. With 275 students, it has one class for Pre-K and two classes per grade beyond that, with an average of 18 students per class. The school has 14 classroom teachers, 4 specialists (music, art, library media specialist, physical education/health), two education case managers, one reading specialist and one reading and math interventionist.

Superintendent Leggett said they have not noticed a change in student achievement since the pandemic. The New Hampshire Student Assessment System (NHSAS) data supports her statement. The NHSAS is administered yearly to students attending traditional public and charter schools in grades 3-8.

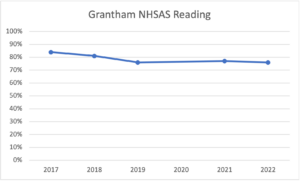

The Grantham NHSAS Reading chart (below) shows that 84% of GVS students scored proficient or above in reading in 2017. That percentage fell to 76% in 2019. In 2021 it rose to 77%, declining very slightly to 76% in 2022. Clearly, GVS’ scores weren’t affected by the pandemic shutdown. Still, though GVS students are significantly outperforming NH’s statewide reading scores, one out of 4 students aren’t reading at grade level.

Leggett said this performance is the result of the community working strongly together to focus on student needs. The school held an expanded summer program for two years in a row, for those who didn’t normally attend summer school, so they could keep building skills. Paraprofessionals had individual contact with students for a year and a half during the pandemic period.

Leggett commended the many parents who created an environment in their homes to help students learn.

One parent, who spoke with me on the condition of anonymity, said that many parents in this wealthy community were hiring tutors or paying for online supplements to help their children learn to read before the pandemic; something common in affluent communities across the country. This is also supported by the podcast series “Sold A Story” (cited below) as being a regular occurrence. The pandemic shutdown caused more parents to engage outside services.

It is well known that when parents are involved in their children’s learning, they perform better in school, although hiring tutors isn’t what people usually think of when they say “involved.” This may account for the above average performance of GVS students on the NHSAS.

For reading instruction, GVS started using the Fountas & Pinnell (F&P) “cueing” curriculum about 7 years ago. The idea behind “Cueing Theory” is that it’s easier for children to learn to read if they start with whole stories and whole sentences and do not try to read individual words. Teachers cover up words in a story and tell students to look at the picture, look at the first letter, and think of a word that makes sense. The theory says that by practicing this approach, children can figure out how to read on their own.

The science of reading research indicates that this isn’t how good readers learn to read, but rather how poor readers try to compensate for not being able to read. The science of reading research is summarized in an engaging podcast series called “Sold a Story,” produced by Emily Hanford, an investigative education journalist at American Public Media.

Leggett said they realized, after a few years, that the F&P program was not providing students with foundational early reading skills. They now supplement it with other programming that focuses on decoding and phonological awareness. The science of reading supports teaching early readers how to decode and learn the sounds that letters make. It also found that, if cueing is the main approach, students still may not learn to read fluently.

Grantham Village School is still trying to improve student literacy. The majority of the staff took the NH Department of Education intensive LETRS training last year — Language Essentials for Teaching Reading and Spelling. LETRS helps teachers understand the science of reading in order to help them teach better.

While the science of reading has shown that the cueing approach is misguided and might harm children, even if used with other methods, Leggett said that GVS continues to use Fountas & Pinnell for the parts they think are worthwhile.

The school now also uses FUNdations, which follows the science of reading. Leggett said that FUNdations has been working well for them. It uses the MTSS (Multi-Tiered System of Support) program to measure reading, math and social-emotion learning. Instructional teams meet with their interventionist regularly to group students by their needs, according to the data.

Superintendent Leggett said it’s not always about the program, it’s about the instruction.

— This story is part of a series in which we show how the pandemic shutdowns in Vermont and New Hampshire affected student performance on state and national standardized tests. We’re also taking a look at how some elementary schools in our area teach reading. Next, we’ll present the final installment in this series, which will include conclusions based on the data. Prior installments in this series were published in the Eagle Times on September 9, 12, 14, 16, 19 and 21.

This article was originally published by the Eagle Times. It has been edited slightly.