I printed these up to hand out at our annual district meeting tomorrow. I thought I’d post it here in case anyone else wants to try something similar in another district.

Budget, or Ransom?

Croydon School District Meeting

March 12, 2022

What we’re being asked to vote on today isn’t a budget. You all know how a budget works. You’re given some amount of money to work with — your salary, your pension— and you find a way to live within those limits.

What we’re being asked to vote on is a ransom. You also know how a ransom works. You’re told that if you don’t pay some amount that is being demanded, someone or something will be taken from you.

I propose that we amend the amount in Article 2 to reflect a budget — that is, the amount that the voters in the district want to pay — rather than a ransom — that is, the amount that district officials feel like demanding.

So what would a reasonable amount be? To answer that, it helps to have some historical perspective.

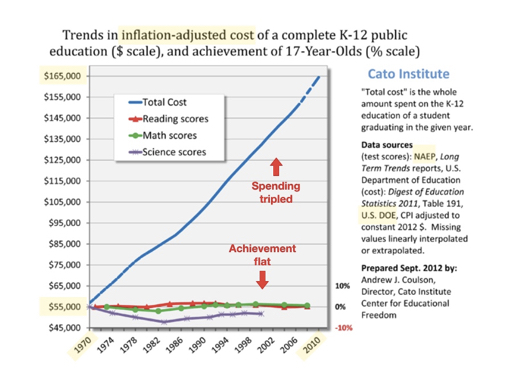

This graph confirms what many people suspect: that there is no correlation between what we spend on education, and the results we get. These are the government’s own numbers, adjusted for inflation.

Over a period of half a century, we’ve more than tripled spending, with no increases in student achievement — as measured using tests designed by the people who claim to be experts in how to educate children.

We could triple it again, and we would have no reason to expect things to get better.

Similarly, we could cut it to 1/3 of what it is, and we would have no reason to expect things to get worse.

We all know that money can’t buy love. Turns out, it can’t buy education, either.

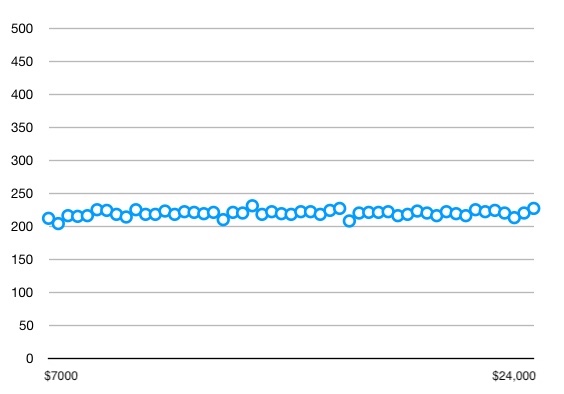

Here is a graph of what each state spends, on average, per student, plotted against those same scores. There are a couple of things to notice.

First, no state is getting the equivalent of a passing score.

Second, all states are getting pretty much the same score, regardless of what they spend. States that spend $7000 per student get the same results as states that spend three times as much.

In a very real sense, it doesn’t matter what we choose to spend.

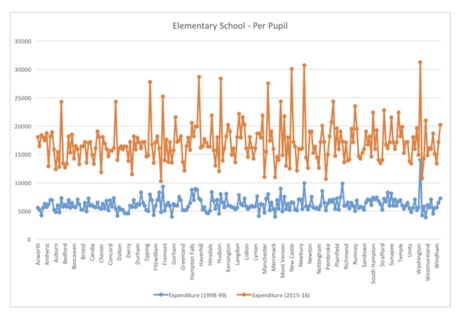

Adjusted for inflation, all districts are now spending more than the richest districts were spending before the Claremont decisions. About $10,000 more per student, on average.

In terms of spending, every district is a rich district. And it hasn’t made any difference at all.

So how do we choose a number? Here are some numbers for comparison:

- The legislature (RSA 198:40-a) has said that the cost of an adequate education is less than $4000 per student.

- The state gives each charter school less than $8000 for each student.

- Newport Montessori and Mount Royal charge less than $9000 per student — and the latter, at least, gives substantial discounts for additional students from the same family.

- VLACS charges nothing.

So $10,000 per student seems like it should be more than enough to educate a child, doesn’t it?

We currently have a little less than 80 students. If we round up to 80 (to be ready in case some children move into town), a figure of $10,000 per student gives us a budget — not a ransom — of $800,000.

Therefore, I propose that we amend Article 2 in the district warrant by changing the amount from $1,705,496 to $800,000.

There are a lot of fundamental questions that never get serious consideration under the ransom-based model of school funding. One such question is: Why are we doing this in the first place?

The state supreme court, in the Claremont decisions, stated that it is the responsibility of the state to

provide each educable child with an opportunity to acquire the knowledge and learning necessary to participate intelligently in the American political, economic, and social systems of a free government

Leaving aside the question of whether the state has any responsibility towards children who are not ‘educable’; and the observation that any child with a computer and an internet connection has the opportunity to learn practically anything that there is to learn; we can ask what it means to take the word ‘necessary’ seriously in this context.

The simplest, most straightforward way to do that is to admit that if some knowledge and learning are not required by everyone, then the state has no responsibility to pay for anyone to learn them.

Can you participate intelligently in the political, economic, and social systems of a free government if you can’t read, write, understand statistics, follow and construct a logical argument, and recognize a specious one? No, you can’t. So learning to do these things is necessary, and taxes may be used to pay for students to learn them.

Can you participate intelligently in the political, economic, and social systems of a free government if you can’t speak a foreign language, play a sport or a musical instrument, calculate a derivative, weld two pieces of metal together, or set up a spreadsheet? Yes, you can. So learning to do these things is not necessary, and using taxes to pay for students to learn them crosses the boundary between public benefit and private charity.

Or to put that another way: Unless everyone needs to learn something, no one can be compelled to pay for students to learn it.

Here are some other questions that need to be considered:

- If a kid wants to learn something, can anyone stop him?

- If a kid doesn’t want to learn something, can anyone make him?

- What is the difference in cost between (1) teaching kids to read, then letting them learn specific course content by reading, and (2) paying teachers to read that content to students who can’t read it?

- Does it make sense for poorer people to pay to educate the children of richer people?

These are all questions that can safely be ignored as long as districts are funded using ransoms instead of budgets.

Will it be difficult for our school board to find a way to get by with $10,000 per student? Only if it tries to keep taking the same failed approach.

The point of putting them on a budget is to force them to find ways to use an entirely reasonable amount of money to accomplish, not what parents would like, but what all of us need.