The recent report ‘New Hampshire Department of Education Long-Term Comprehensive Modeling Analysis of Education Freedom Accounts’ is supposed to show how Education Freedom Accounts (EFAs) can save taxpayers a bunch of money.

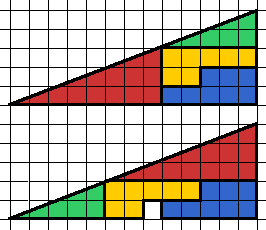

But while reading it, I was reminded of a puzzle that we were often asked about at Ask Dr. Math, which is pictured above. By rearranging the pieces in the first triangle, we get a second triangle with a different area. How can this happen?

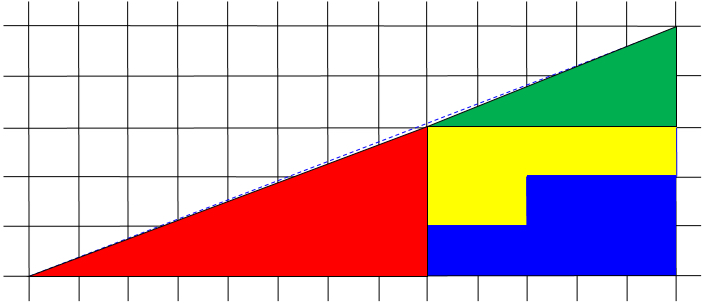

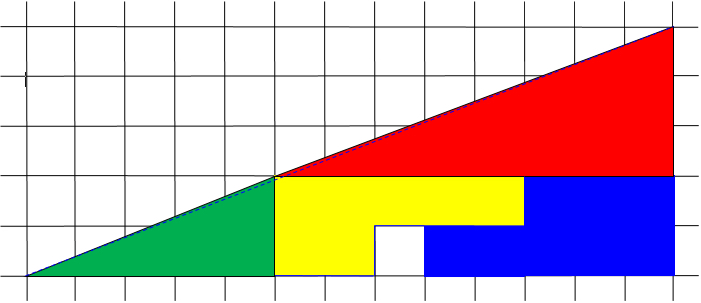

Here are the same figures shown a little larger, and with thinner lines.

In the first triangle, moving from left to right, you move at one slope (3/8), and then switch to a steeper slope (2/5). This means that the ‘hypotenuse’ is not actually a straight line, but in fact is slightly concave. In the second triangle, the situation is reversed: you switch from a steeper slope to a gentler one, which makes the ‘hypotenuse’ slightly convex.

So in fact, neither of the ‘triangles’ is really a triangle at all. Each is a quadrilateral in which one of the angles is nearly 180 degrees. The thickness of the line in the original figure is used to mask the change in slope; but the area between the convex and concave ‘hypotenuses’ is the area of the white square in the bottom triangle.

So what’s the connection between the puzzle and the report? The report does something very similar.

The DoE acknowledges that the average per-student cost in the state is $19,874, but hedges that by saying that some part of that cost — ‘as high as $13,350’ — is variable.

No argument there. You can vary the per-student cost by hiring more or fewer teachers, spending more or less on transportation and sports and other extra-curricular activities , changing how you run the cafeteria, and so on. But it’s not whether costs are variable that’s important. It’s what the marginal costs are that matters.

The DoE bases its estimated savings on the idea that somehow, when a kid leaves a public school district to become an EFA student, as the hole left by his absence percolates through the system, it will result in reduced costs for the district. After three years, the district will be saving the $13,350 that it used to ‘spend on the kid’.

To make this a little more concrete, suppose a district offers grades 1-5, each with 20 students. Now, suppose one of those kids leaves to become an EFA student. According to the DoE, the situation looks like this:

| Year | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Savings |

| 1 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | $0 |

| 2 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 20 | $4,450 |

| 3 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 20 | $8,900 |

| 4 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 20 | $13,350 |

That is, the DoE claims that the cost of running the school after 3 years will be reduced by the variable per-student cost of the student who left. The district will realize that reduced cost as savings.

But how, exactly, is that supposed to happen? Where do those savings come from? Which of those variable costs is going to be reduced by $13,350? Staffing? Transportation? Sports and other extra-curricular activities? The cafeteria?

It’s like the puzzle — by merely rearranging the pieces, we get a hole where we didn’t have one before!

The variable costs are all going to stay the same, just as they would if another kid showed up. The marginal savings from losing a student are the same as the marginal costs of adding a student. Both are zero. And where small numbers of students are involved — which is a premise of the EFA program — it’s only the marginal costs that matter.

So the district doesn’t save money on the school; and it spends extra money on the EFA student. But when accumulated across the state, this is supposed to translate into a savings of millions of dollars. It’s a little like the punchline to the old joke: We lose a little money on each sale, but we make it up on volume.

The real question is whether the people who put together the analysis (1) don’t understand this, and are misleading you by accident, or (2) do understand this, and are misleading you on purpose… like in the puzzle.

To be clear: I’m not saying that it’s a bad thing for students to have opportunities other than the ones that are assigned to them based on where their bedrooms happen to be located. Or that EFAs would be a bad way of providing those opportunities.

But if we’re going to have a rational discussion of EFAs, proponents shouldn’t undermine their credibility at the outset by pretending that EFAs are going to save money, when in fact they’re going to increase spending.

EFAs need to be debated on their merits — which may be many, but which do not include saving money.