Every once in a while, you come across a simple idea, or a simple question, that changes how you think about almost everything. Paul Goodman once asked a question like that, which is most easily illustrated with a simple curve.

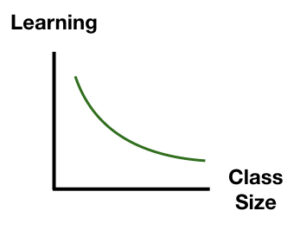

Imagine a situation where we think that less of something is better. For example, we would expect that as the number of students in a class goes down, the amount that the students learn would go up. We can illustrate that with a curve that looks like this:

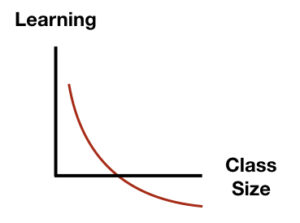

So if we have larger classes, that’s not as good for the kids, but it’s still better than nothing, right? But that was exactly Goodman’s question: What if it’s not better than nothing? That is, it’s possible that the curve actually looks like this:

It could be that the teacher, overwhelmed by too many students, teaches in a way that makes the material (and perhaps other material in later courses) harder, rather than easier, to understand. We would call that ‘doing more harm than good’.

Also, while the students are failing to learn the material, they are wasting time that they could have spent learning something else. We would call that a ‘lost opportunity’, or an ‘opportunity cost’.

In either case, the kids are actually worse off for having been in the class.

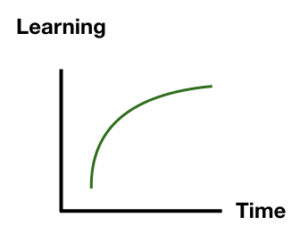

Something similar can happen in situations where we think that more of something is better. For example, many people believe this about the number of hours in a school day, or the number of school days in a year:

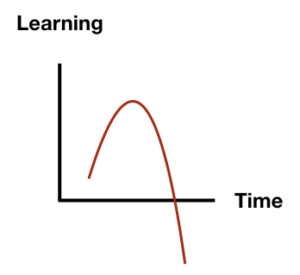

But it could also look like this:

Research suggests that every time a student walks out of one class and into another, trying to learn the material in the second class will interfere after the fact with the learning that happened in the first class.

This idea — that we might be making things worse, rather than better — is obvious enough when you see it explained, but the difficulty isn’t in understanding it. The difficulty is in remembering to ask the question in the face of conventional wisdom.

So here’s a test, to see if you’ve really grokked this idea:

Could it be the case that spending more money on schools actually makes things worse, rather than better?

Are you dismissing this notion out of hand, as being too outrageous to consider? If so, you may as well stop reading now.

Or are you seriously considering some of the ways in which the answer might turn out to be yes? If so, congratulations!

You may have seen this graph before:

Over a period of about 50 years, we’ve tripled per-student spending (adjusted for inflation), and have seen absolutely no measurable increase in student achievement.

This strongly suggests that it doesn’t really matter too much what we do in schools: what pedagogical methods or assessments we try; what technology we introduce; how much individual attention we give to students; and certainly how much money we spend on all that.

I think that when we combine Goodman’s question with the data in the Cato graph, we have to seriously consider the possibility that many kids end up learning less than they would if they just didn’t go to school at all.

Another way to say that is: For many kids, maybe school doesn’t provide an opportunity, so much as it imposes an opportunity cost.

You can dismiss that idea out of hand, and I expect that most people will. But then you have to come up with a better explanation for the Cato graph. Oh, and an explanation for the results of Sugata Mitra’s Hole in the Wall experiments in India. (If you don’t know about those yet, please follow that link.)

One of the basic ethical principles of medical care is nonmaleficence, which is often expressed more prosaically as first do no harm.

As mandated by the courts¹, what we’re supposed to be doing is providing

each educable child an opportunity to acquire the knowledge and learning necessary to participate intelligently in the American political, economic, and social systems of a free government.

In a world where educational resources like books and teachers were scarce, providing such an opportunity required active steps, i.e., bringing kids to central locations where they could share those resources. But we don’t live in that world anymore.

In the world where we live, a smartphone and an internet connection put you a few clicks away from the collected knowledge of mankind, and queues of people lined up to teach you anything you want to learn, often for free.

In the world in which schools were invented, opportunities to acquire knowledge required you to travel to where they were.

In the world where we live now, those opportunities are literally falling from the sky around you, wherever you happen to be, and whenever you want them.

So when we shuttle kids to institutions where they have access to fewer and lower-quality educational resources than they had at home, and where bullying is the main organizing principle — that is, to schools — does that sound like doing no harm?

¹ But not the constitution.