In thinking about the arguments that have been made in support of the recent rejection of $46 million in startup funds for new charter schools in New Hampshire, it helps to understand some basic facts about how school districts and charter schools are funded.

There are two principal sources of revenue for a district. The first is the State Wide Education Property Tax (SWEPT), which is collected by districts at the direction of the state. This applies a standard rate (about $2 per thousand) to all the eligible property in the state, with the goal of raising a specified amount of money (around $300 million) statewide. Although considered a state tax, the money never actually leaves the district.

This tax is used to provide so-called ‘adequacy funds’ to each district — about $3600 for each student who attends a district school.

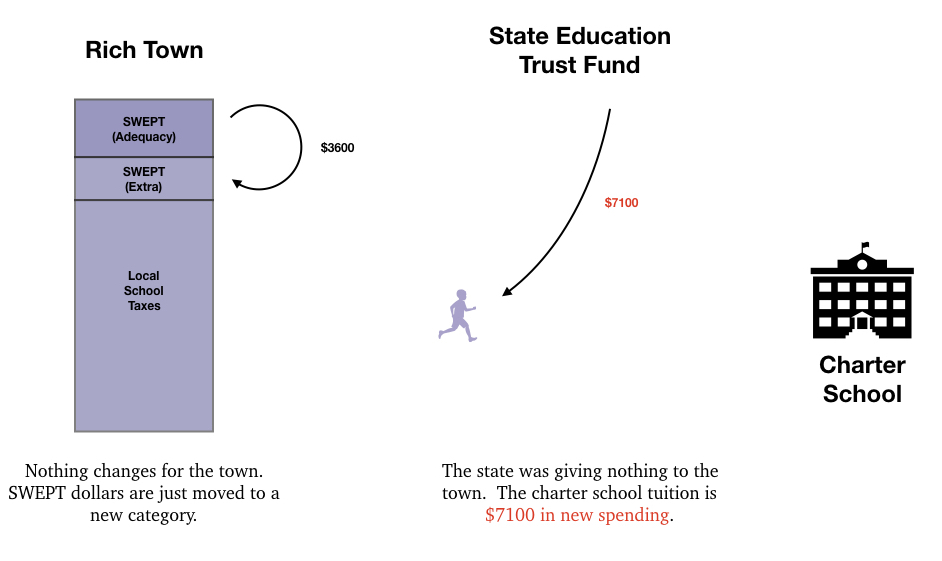

In a property-rich district, the amount raised by SWEPT is greater than the amount needed for adequacy funds. The excess is applied to the district’s budget, and the district receives no adequacy funding from the state.

In a property-poor district, the amount raised by SWEPT is less than the amount needed for adequacy funds. The shortfall is made up by a grant from the state education trust fund.

The difference between the budgeted amount and the adequacy funds is made up by local school taxes. Each year, the district sets a tax rate (some number of dollars per thousand) that is applied to the eligible property in the district in order to make up this difference.

A charter school receives $7100 in tuition for each student who attends the school. All costs — teaching, maintenance, operations — are covered by this amount. This money comes from the state education trust fund.

With all this in mind, we can ask: What are the fiscal consequences of a child leaving a regular public school to attend a charter school?

When a student leaves a regular public school to go to a charter school, it costs the state either $7100 or $3500 in new spending, depending on whether the district has an excess or a deficit of SWEPT funds.

If there’s an excess, the $3600 in SWEPT that would have been categorized as adequacy funding for that student is simply recategorized as excess funding. In either case, it gets applied to the district budget. The state has to come up with $7100 in new spending from the state education trust fund to pay tuition to the charter school.

If there’s a SWEPT deficit, the $3600 that the state would normally give to the district for that student is given instead to the charter school. Since the district budget is not reduced by the loss of the student, it has to recover that money from residents. The state has to come up with an additional $3500 in new spending from the state education trust fund to pay tuition to the charter school.

So the migration of 4000 students from regular public schools to charter schools would be expected increase yearly expenditures from the state education trust fund by between 14 million and 28 million dollars.

These are ongoing yearly costs. They do not include the startup costs that would be covered by the $46 million federal grant being considered.

There is no question that doubling the number of charter schools in New Hampshire would cost taxpayers a considerable amount of money.

What is a question is whether the money would be well-spent. After all, neither of the major parties seems to have any real problem with spending scandalous amounts of money for skimpy results.

How scandalous? When you factor in all costs, the average per-student spending in NH is about $18 thousand. Over the course of 12 years, that comes to $216 thousand, which is more than 3/4 of the median price of a home in NH.

How skimpy? Consider that although the graduation from regular public schools is above 90%, only about 40% of those graduates have reached the most basic level of proficiency in fundamental subjects like reading and math.

In comparison, if every student attended a charter school, our per-student cost would be about $7100 per year, or about $85 thousand over the course of 12 years. Still way more money than it should cost to help kids learn to read, write, and reason; but a hell of a lot less than we’re spending now.

NEA-NH recently rationalized rejecting the grant because it would benefit only a relatively small number of students, and not ‘the overwhelming majority’ of students. But that logic seems flawed. For example, if we were able to secure a $46 million grant to help blind students, then following the same reasoning, NEA-NH would have to recommend its rejection too, since the overwhelming majority of students are not blind. Similarly, NEA-NH would have to recommend rejecting any grant targeted at students with special needs. So this doesn’t seem like a serious objection.

A second rationalization offered by NEA-NH is that decisions about charter schools should ‘rest with the legislature’. But the legislature has already spoken, and spoken clearly on the subject, via RSA 194-B. And its decision was to leave oversight of charter schools to the professionals in the Department of Education, instead of leaving it to part-time legislators who often have little or no understanding of the subject. So this seems like a strange objection for an association of education professionals to be making.

A third rationalization offered by NEA-NH is that charters are not ‘subject to the same transparency requirements and safeguards as our neighborhood public schools’. But that’s the whole point of charters, isn’t it? They exist — and RSA 194-B encourages their creation — precisely because those requirements and safeguards have led, not to transparency and safety, but to opaqueness and vulnerability, all while making it harder, rather than easier, for kids to actually be educated.

Which brings us to the central question about charter schools: How do they perform, relative to regular public schools? As in any other area of public policy, there are lies, damned lies, and statistics. So on the one hand, no one’s mind is going to be changed by a study that claims to show that charter schools are ‘better’ than regular public schools.

But on the other hand, no one is going to argue that charter schools are worse than regular public schools! For starters, given the track record of regular public schools, that hardly seems possible.

What derails any substantive conversation about school funding is the automatic presumption that the existing public school system is doing an excellent job, implicitly positioning any alternative as some kind of dangerous experiment.

But we need to compare apples to apples. We need to compare, not the ideal outcomes of regular public schools and their alternatives (which all sound wonderful), but the expected real outcomes of regular public schools and their alternatives. And in the case of regular public schools, we have a track record that tells us what those outcomes have always been, and are always likely to be.

That is, when considering an alternative, we need to ask: Would the alternative be able to produce better than a 90% graduation and 40% proficiency rate among its students? And would it cost significantly less than what we’re spending now? If the answers are yes and yes, then the alternative passes what we might call the 90/40 Test.

And if the results aren’t any worse, but the costs are lower, why in the world wouldn’t we go with the lower-cost alternative?

Charter schools pass this test — but only if we have enough of them that they can replace a sufficient number of regular public schools.

So the wrong question to be asking is: Should we have more charter schools? The right question to be asking is: Why should we have anything but charter schools?

After all, if every regular public school were converted to a charter school, not only would total spending be slashed, but local property taxes would drop dramatically, since the entire burden of paying for schooling would be shifted to the state. And this shift, to paraphrase Bastiat, would bring us closer to the true goal of school funding: to let everyone live at the expense of everyone else.