Long ago, I read an account about some factories in the Soviet Union that made cookware for soldiers. Of course, if you’re a soldier, you’d like your cookware to be as light as possible, because you’re going to be carrying it around. And you want it to heat as quickly as possible, because you have to either find or carry your fuel.

However, the managers of these factories were rewarded, not for producing lighter cookware, or better cookware, or more cookware. They were rewarded for using more raw materials. The more raw materials a factory consumed, the more highly its managers were rated.

Can you guess what happened?

The factories started making the cookware as heavy as possible! Harder to carry, harder to use. Life got worse for the soldiers, and worse for the rest of society, but better for the managers.

Funny, right? Those crazy communists! But we do the same thing with our schools that they did with their factories. That is, our schools are rewarded, not for teaching kids more, or teaching them more quickly, but for consuming more student time.

As a thought experiment, imagine that the faculty of some high school figures out a way to get students through the entire curriculum in three years instead of four¹.

Now, for each student who graduates a year ahead of time, the school would lose state adequacy funds for that student’s fourth year, amounting to about $3600. For a school with around 300 kids in each cohort, adopting this new approach would mean a loss of more than $1 million a year in state funds.

Can you guess what would happen?

First, it’s nearly certain that the education establishment would react with explanations for why adequacy funding should be increased, or supplemented, or stabilized, rather than reduced. Second, it’s only slightly less certain that it would follow this up with proposals (such as new requirements for graduation) to increase the required time back to four years.

Financially, it always makes sense for a school — or any other institution funded with tax money — to try to accomplish less, or use more resources, or both. No matter what its stated goals are, its incentives will always move it in that direction².

It’s almost Orwellian: success (in terms of results for the students) is failure (in terms of rewards for the school).

It cannot be said too often: Politicians and bureaucrats think in terms of goals, while people respond to incentives. Unfortunately, it’s all too often the case that goals and incentives point in opposite directions. When that occurs, incentives always win. It happened in those Soviet factories. And it’s happening now in our schools.

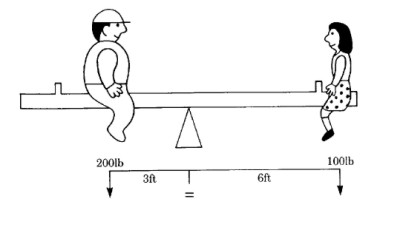

One of the nicest illustrations of the difference between goals and incentives that I’ve ever seen is described in one of John Holt’s books. Holt was observing some students who were doing a lesson on how beam balances work. The students were supposed to discover the rule for making the two sides balance³:

But instead of being rewarded for making the beam balance, the teachers cleverly decided to reward the kids for making correct predictions.

Can you guess what happened?

The easiest way to make a correct prediction is to set up a situation that you know isn’t going to balance, and then predict that it won’t balance. The kids figured this out very quickly, and began racking up points as fast as they could fail, coming up with some clever strategies for generating failures.

Did they learn how to make a beam balance? No. But you can’t really fault them for that, because the children were responding, not to the goals of the teachers, but to the incentives they were given.

That’s how people work. They respond, not to goals, but to incentives.

Until we change the incentives that we give to our schools, it doesn’t matter what lofty goals we proclaim, or how much money we spend, or where we get it from. If we cling to Soviet-style incentives, we’ll continue to get Soviet-style results.

¹ Which, honestly, wouldn’t be all that hard, if the kids spent the first year learning to read with speed and comprehension, allowing them to absorb subsequent course content by reading instead of by listening. Reading is typically between two and ten times faster than listening.

² I first experienced this when working at NASA. When the end of the fiscal year rolled around, we would be asked to find ways to spend any money that had been budgeted but not used. Does anyone need new computers or software? Office furniture or supplies? Should we go on a retreat? If you didn’t spend your entire budget, you could expect to see it reduced in subsequent years.

³ The product of the weight and the distance from the fulcrum has to be the same on both sides.