In 2025, the public appetite for cutting unnecessary government expenses, improving efficiency and reducing taxpayer liabilities is enormous. Inflation put tremendous stress on household finances as COVID-era regulatory and spending decisions tanked Americans’ trust in government management. In New Hampshire, policymakers are looking for new ways to deliver core services at lower costs.

One reform that would lower taxpayer liabilities while improving services is switching from a traditional defined benefit (DB) pension to a defined contribution (DC) retirement plan for new state employees. This would be a responsible way to create long-term savings without cutting state services. DB plans obligate taxpayers to finance specific payouts to public employee retirees even if the state failed to fully fund those payouts. DC retirement plans, which most private-sector employees (thus, most taxpayers) have, can provide retirement benefits at lower costs and lower risk.

This policy brief offers five reasons to consider creating a DC retirement plan for new state employees.

1. A DC plan avoids future unfunded pension liabilities

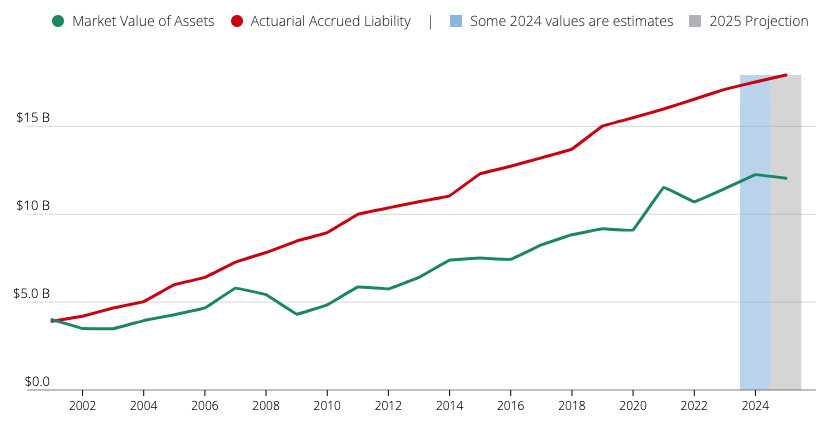

The New Hampshire Retirement System is a defined benefit pension plan in which employees are promised specific payouts after retirement. The state must pay these obligations even if it failed to fully fund them or the plan’s investments didn’t generate enough revenue to meet them. Currently the retirement system’s unfunded liabilities are about $5.6 billion. The design of this system creates future unfunded obligations that must be paid (if the state keeps its word). In other words, debt. That debt obligation falls on taxpayers. This chart from the Reason Foundation’s Annual Pension Solvency and Performance Report shows the steady gap between New Hampshire’s pension assets and liabilities.

Instead of obligating taxpayers to finance a fixed annual payment decades in the future, DC plans create investment accounts into which the state deposits fixed amounts. The taxpayer is obligated to make an investment up front, rather than a determined payment at the end. Because the taxpayer obligation comes from the initial investment, DC plans don’t have unfunded liabilities.

2. Pension liabilities crowd out other needs

Government pension benefits are typically treated lavishly in contract negotiations, but not fully funded later. That creates debt obligations that crowd out other services as governments divert funds to pension obligations. A 2024 University of Texas study of the effects of pension liabilities on California cities found that to free up money for pensions, cities “primarily reduce non-current expenses, specifically capital investment.” They also “cut payrolls and employment, with police employment declines specifically. Further, there are accompanying increases in crime rates. These estimates imply that pension pressure impairs local public service provision, with contributions displacing other spending.” During testimony this year on a bill to allow open enrollment in K-12 public schools, the president of the N.H. chapter of American Federation of Teachers underscored the point made in the study above. She opposed the bill, she said, because districts had to maintain enrollment to fund pension obligations. A pension system that discourages innovation is one that serves neither taxpayers nor citizens well.

3. DC plans offer portability & earlier vesting

The old-fashioned public-employee pension plan is not designed for today’s mobile workforce. It’s not even designed well for older workers. A U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics study of Americans born between 1957-1964 found that they averaged 12.7 jobs over their careers. Members of Gen. Z are expected to have an average of 18 jobs over their careers. A BLS study last year found that wage and salary workers spent a median of 3.9 years with their current employer. Few employees, public or private, stay in one job for even a decade, much less their entire careers.

It takes 10 years for state employee pensions to vest, but most state employees don’t last that long. A 2024 Reason Foundation study of public pension plans in 12 states found that 62% of public workers leave before their pensions vest. Many people believe it’s compassionate to offer public employees a generous DB pension. But a pension system designed so that the large majority of public employees will never vest in it is not a good deal for most public employees. DC plans vest much earlier, usually within a few years, and could vest immediately. DC plans also are heritable if an employee dies, unlike DB plans.

4. Pensions are more costly and less safe than assumed

Defenders of DB pensions claim that traditional pensions are safer than DC plans. State Employee Association President Rich Gulla testified in January that New Hampshire shouldn’t adopt a DC plan for state employees because such a plan would be invested in stocks, which risk losses. Asked if the New Hampshire Retirement System invested in the stock market, he said he didn’t know. It does. In the 2024 fiscal year, 51.3% of NHRS funds were invested in equities.

How did those investments do? According to the system’s annual report, the 8.8% return on total investments “underperformed the total fund custom index (a blended composition of major market indices in proportion to the NHRS’ asset allocation), which returned 11.9%.” The equities portion of the NHRS portfolio underperformed the market in FY 2024 as well. “Domestic Equity generated a return of 19.0%, underperforming the Russell 3000 Index return of 23.1% by 420 basis points. The non-U.S. equity portfolio returned 11.3% during fiscal year 2024, underperforming the MSCI All Country World (ex U.S.) index return of 11.6% by 30 basis points,” the annual report stated.

Trading lower returns for a guaranteed payout isn’t necessarily a great deal, especially for younger employees. The NHRS was just 68.6% funded in FY 2024. A January study by the Equable Institute had our funded ratio slightly higher, yet still ranking just 41st in the country. Contrary to the messaging of public employee union leaders, state pensions are far from secure, and New Hampshire’s is one of the least well-funded in the country. A Pew Charitable Trusts analysis concluded that New Hampshire had to dedicate 9.4% of the state’s own-source revenue ($512 million) annually to cover pension obligations.

And that’s if our liability estimates are correct. A 2024 Stanford University study of public pensions concluded that they were in far worse financial shape than official data suggest because “future pension obligations are being grossly undervalued.”

The problem is structural, the study concluded, and the lead author recommended that “states and cities could move to defined contribution plans similar to those offered by private employers. Employer contributions could still be quite generous, but the plans would be much less expensive to run because they would not guarantee a preset lifetime benefit.”

5. DC plans can lower costs and achieve solvency

The average N.H. state employee pay is $65,360, which is just $750 less than the average for the state as a whole ($66,110). It’s hard, then, to justify making taxpayers shoulder the burden of financing expensive guaranteed pensions they don’t enjoy themselves. With a DC plan for new state employees, this discrepancy would end, and the plan would be easier to fully fund.

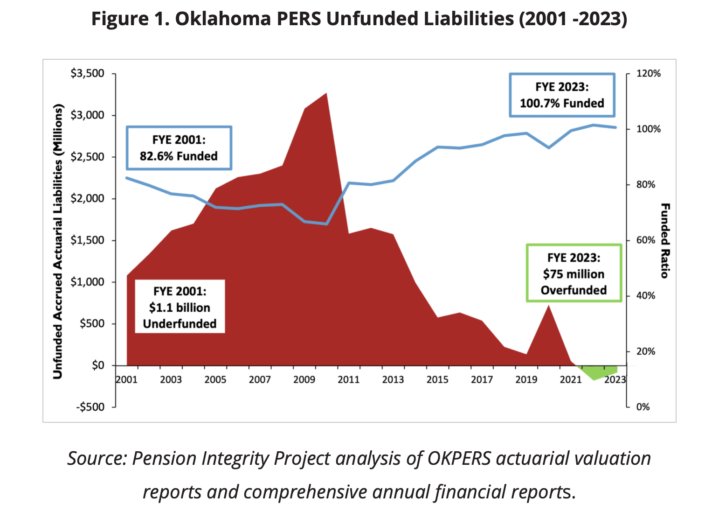

In 2010, the Oklahoma Public Employees Retirement System was in a similar position to New Hampshire’s. Oklahoma’s system was only 66% funded. Legislators made two critical reforms that changed the trajectory of the system, the Reason Foundation reported. They ended future cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) benefit increases that weren’t fully funded in advance. And in 2015 they shifted new employees to a DC plan. (In addition, they kept the state contribution to both plans at 16.5%.)

The Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project charted the effects of these changes to Oklahoma’s system (shared below).

Conclusion

New Hampshire’s state pension system is a relic of a bygone era. As Oklahoma took its system from 66% funded to fully funded by making critical reforms that featured creating a DC plan for new hires, New Hampshire’s has limped along with no substantial improvement in its funded ratio. Taxpayers remain on the hook for $5.6 million in unfunded liabilities while state employees have to put in a decade of service to vest in a plan that doesn’t generate great returns.

Creating a DC plan for new state employee hires is a financially sound way to lower state costs, stop crowding out other government programs, reduce taxpayer obligations and create a fully funded, portable retirement plan that doesn’t take a decade to vest.

Download this policy brief here: JBC Brief DC Retirement Plans March 25

As a reminder, authors’ opinions are their own and may not represent those of Grok Media, LLC, GraniteGrok.com, its sponsors, readers, authors, or advertisers. Submit Op-Eds to steve@granitegrok.com

Donate to the ‘Grok to keep the content coming.