Imagine that you’ve just graduated high school or college, you’ve landed an entry-level job, and you need a car. What’s on your car shopping list?

It’s your first job, so you’re probably looking for a cheap car, and smaller cars are cheaper to buy and maintain than larger ones.

So you start shopping. To your surprise, you find zero small cars for sale. It’s all full-size SUVs and pickups as far as the eye can see. You ask a salesman where to find the coups and sedans.

Oh, he’d love to sell you a small car, he says, but he can’t. Every town in the area has a “minimum chassis size” ordinance. They require every vehicle to be at least 16 feet long by 6.5 feet wide.

But you don’t want a Chevy Tahoe, you protest. You don’t need a big SUV. You don’t have a big family, or even a dog. You just want a small hatchback that’s good on gas. Why would the town make you buy a larger car than you need?

Oh, that’s easy, he says. Town character.

It’s a family community. If the town let dealers sell small cars, why, young, single people might move there. The character of the town could change. People like the town just the way it was when they moved in. So, no small cars.

Absurd, right?

Well, replace automobiles with housing in that tale, and you’ve got the status quo throughout New Hampshire.

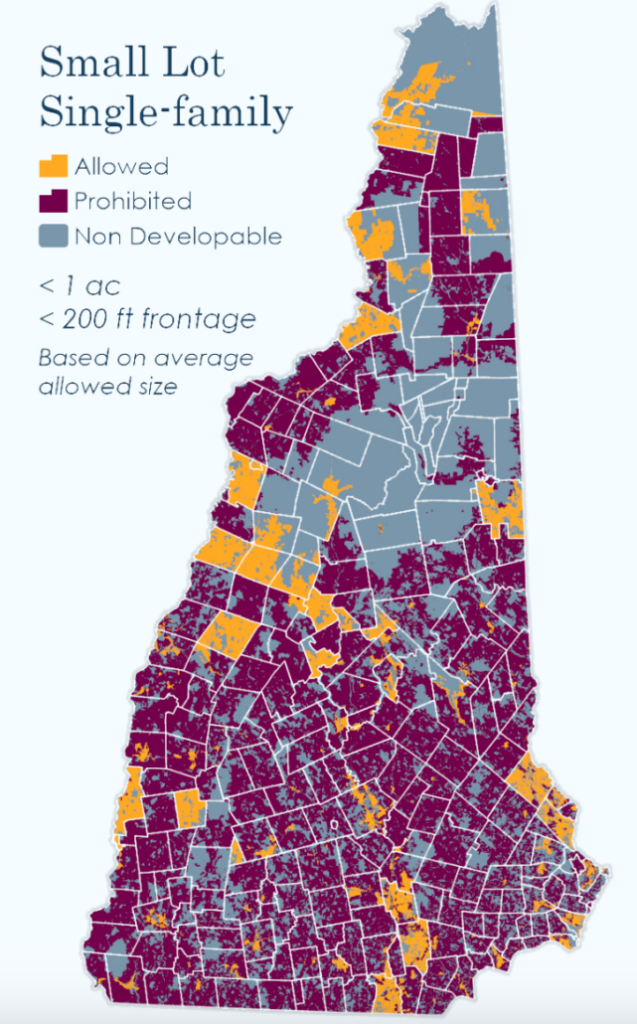

To quote the New Hampshire Zoning Atlas created by St. Anselm College, “it is hard to find land to build small homes or starter homes in an economically viable way.” Only 15.7% of the buildable area in New Hampshire allows homes to be built on less than one acre of land with less than 200 feet of frontage.

These mandated large lots are rarely directly related to public health or safety, which makes them legally suspect.

RSA 674:16 grants local governments the power to use zoning “for the purpose of promoting the health, safety, or the general welfare of the community….”

“General welfare” is vague, but surely it doesn’t include raising the cost of buying a home in town.

When creating a minimum lot size mandate, there are two questions to ask.

- What public health, safety or welfare problem does this solve?

- How much land does a home require?

The answer to the first question most often is: none. This is especially true in municipalities served by water and sewer infrastructure. A tiny home on a tiny lot harms no one. Small house lots harm no one.

Large lot size mandates do harm people. They raise the cost of land and homes, pricing many people out of the housing market.

The answer to the second question is: not much.

Two bills in the Legislature would fix lot size inflation by prohibiting local governments from mandating large lot sizes that aren’t directly connected to public health or safety metrics. House Bill 459 and Senate Bill 84 vary in the details, but both would tie minimum lot sizes to legally justifiable standards.

SB 84, facing a Senate vote this week, would cap minimum lot sizes at 1.5 acres in areas with no municipal water or sewer service, one acre in areas with municipal water, and 0.5 acres in areas with municipal sewer service.

Minimum lot sizes that are larger than 0.5 acres for properties with water and sewer hookups, or larger than basic environmental standards for single-family homes based on soil conditions, serve only one purpose: to raise housing costs. And in that they are extraordinarily successful.

Large minimum lot sizes have been shown to increase lot sizes, home sizes and home prices. And these government-created price increases spill over into neighboring jurisdictions.

Tighter regulations spread through adjacent municipalities in a zoning arms race that reduces home construction and raises prices throughout states and regions. That’s a big reason why legislators are intervening. The cumulative effect of these local restrictions is a statewide housing shortage.

Maine has roughly the same population as New Hampshire (1.405 million vs. 1.409 million). Yet Maine has almost 106,000 more housing units than New Hampshire does. As a consequence, its median home value from 2019-2023 was $100,000 lower than New Hampshire’s. As of this January, the median sale price for a home in Maine was $412,200 vs. $493,800 in New Hampshire.

The median size of a home in New Hampshire is 1,869 square feet, according to Federal Reserve data. The median size in Maine is 1,669 square feet.

It shouldn’t be harder to buy a smaller, more affordable home in New Hampshire than in Maine. Ending the abuse of lot size ordinances would be an effective way to begin fixing this disparity.

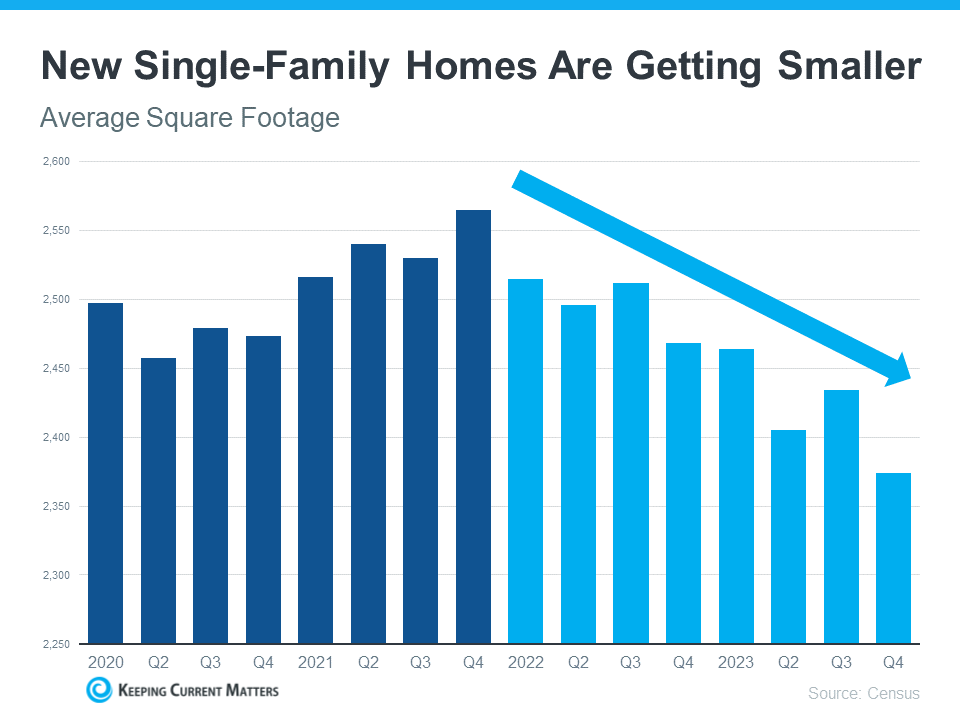

There is huge market demand for smaller homes on smaller lots. In places where these options are legal, developers have responded. Census data show a decline in new home sizes since 2022, as the chart below from real estate website Keeping Current Matters shows.

In 2013, 36% of new homes in the United States were built on a lot of 7,000 square feet or less. By 2023, it had risen to 46%, according to U.S. Census figures.

The average size of a newly built home is slowly shrinking. It has fallen from 2,535 square feet in the second quarter of 2022 to 2,375 square feet in the second quarter of 2024.

The demand for smaller homes is clear, and the market is trying to respond. But municipalities are slowing the transition, particularly in the Northeast.

In the South, 53% of homes sold in 2023 were smaller than 2,400 square feet. In the West and Midwest it was 60%. In the Northeast it was just 46%. That’s not entirely caused by zoning, but zoning is a factor.

Nationally, 26% of home buyers want a home less than1,600 square feet, but only 16% of single-family homes started in 2023 were that small, according to the National Association of Home Builders.

There’s a mismatch between demand and supply, and that mismatch is driven in large part by minimum lot size requirements. Smaller legal lot sizes would facilitate the creation of the smaller homes that consumers demand.

In many places, including most of New Hampshire, it’s literally illegal for builders to construct a home on a lot smaller than an acre.

Minimum lot sizes that exceed basic public health and safety standards artificially reduce the supply of housing, drive up home prices, separate families by forcing the elderly and young to move out of town, worsen sprawl and traffic congestion, and encourage overdevelopment by forcing builders to develop much larger footprints to house people who could live comfortably on smaller lots.

Smaller lots allow for smaller, more affordable homes. Municipalities have shown that if they have the power to use minimum lot sizes to prohibit small homes on small lots, they will. The abuse of this power has created numerous economic problems for New Hampshire and has helped to put the classic American starter home out of reach of young Granite Staters.

If the state wants to prevent these abuses from continuing, the quickest option is to limit the power of local governments to commit them.

As a reminder, authors’ opinions are their own and may not represent those of Grok Media, LLC, GraniteGrok.com, its sponsors, readers, authors, or advertisers. Submit Op-Eds to steve@granitegrok.com

Donate to the ‘Grok to keep the content coming.