Maine stole our land when we weren’t looking. The historical evidence is overwhelming and clear. For almost 300 years, the Granite State’s northern border ran down through the Piscataqua River, snaked across Maine’s Portsmouth Harbor shoreline, then bisected the Isles of Shoals.

New Hampshire’s borders embraced the entire harbor, including Badger’s Island, Seavey’s Island, and even Pepperell Cove—a mile east of the Naval Shipyard. These areas were an unambiguous part of New Hampshire from the founding of colonial New Hampshire in 1679 until the late 20th century—a period of almost 300 years.

Today, these islands and much of the Portsmouth Harbor are treated as part of Maine, where they have been a key economic resource. The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on Seavey’s Island injects $1.5 billion annually into the regional economy, most of which goes to Maine—a state with an annual GDP under $99 billion. Maine also generates millions each year from lobster fishing in its harbor waters.

Yet Maine’s territorial claims are surprisingly shallow. For centuries, no significant legal documents suggested that anyone but New Hampshire controlled any part of the harbor. Maine had no serious legal claim to any harbor waters, let alone the harbor islands, until the lobster-fishing disputes of the 1970s. Maine did not even use garnishment to tax Naval Shipyard workers until 1997.

In contrast, New Hampshire’s centuries of unambiguous control over the harbor lasted longer than the United States has existed. The Granite State controlled the harbor and its islands for longer than Latin American states have been independent from Spain, twice as long as India has been a unified nation, and three times as long as modern African states have existed. Maine’s claim to these areas is younger than the average resident of Wolfeboro.

As surely as any land can belong to any state, the harbor islands are part of the historic soul of New Hampshire. By annexing them, Maine has not only deprived New Hampshire of a valuable economic resource—it has also stolen a fulcrum of New Hampshire’s story, identity, and symbolism. It’s time to reexamine how this territory was lost and what our leaders can do to take it back.

The History of the Harbor Islands

It is undisputed that, when the Province of New Hampshire was founded in 1679, New Hampshire’s colonial government exercised complete control of the entire Portsmouth Harbor. Massachusetts Bay Colony, which controlled the land that is now Maine, did not own any part of the harbor waters. While not all early legal documents delineate a harbor boundary, none claim that any part of the harbor belonged to Massachusetts.

At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, New Hampshire sent its state militia to occupy the harbor islands and build batteries on Seavey’s Island, writing to the Continental Congress for ammunition to defend “our harbor.” These Seavey’s Island batteries grew into a fortification called “Fort Sullivan,” named for Major General John Sullivan—commander of New Hampshire’s forces and later the Granite State’s third governor. The USS Raleigh, the ship depicted on New Hampshire’s state seal, was built in the harbor on Badger’s Island.

After the Revolutionary War, maps show the harbor and Seavey’s Island as part of New Hampshire, including a 1791 map by the famed historian Jeremy Belknap, namesake of Belknap County.

During the War of 1812, New Hampshire continued to use Seavey’s Island and Fort Sullivan to enforce state controls on trade and ship traffic. Meanwhile, Maine was invaded and defeated by the British, who occupied the Pine Tree State until a peace treaty was ratified in 1815.

New Hampshire’s harbor powers included the quarantine of ships, which the Granite State oversaw from 1805 to 1896. Ships were quarantined in Pepperell Cove, a full mile beyond the eastern coast of Seavey’s Island.

Fort Sullivan continued to operate on Seavey’s Island during the Civil War, where it was used to train black Union soldiers. In 1864, the USS Alabama was refitted on Seavey’s Island for these soldiers and rechristened the “USS New Hampshire”—later renamed the “USS Granite State.”

Fort Sullivan was dismantled in 1866. During the 1898 Spanish-American War, however, the makeshift “Camp Long” was built on Seavey’s Island, where it was used to house 1,600 Spanish prisoners of war. This camp was widely understood at the time to be on the territory of New Hampshire.

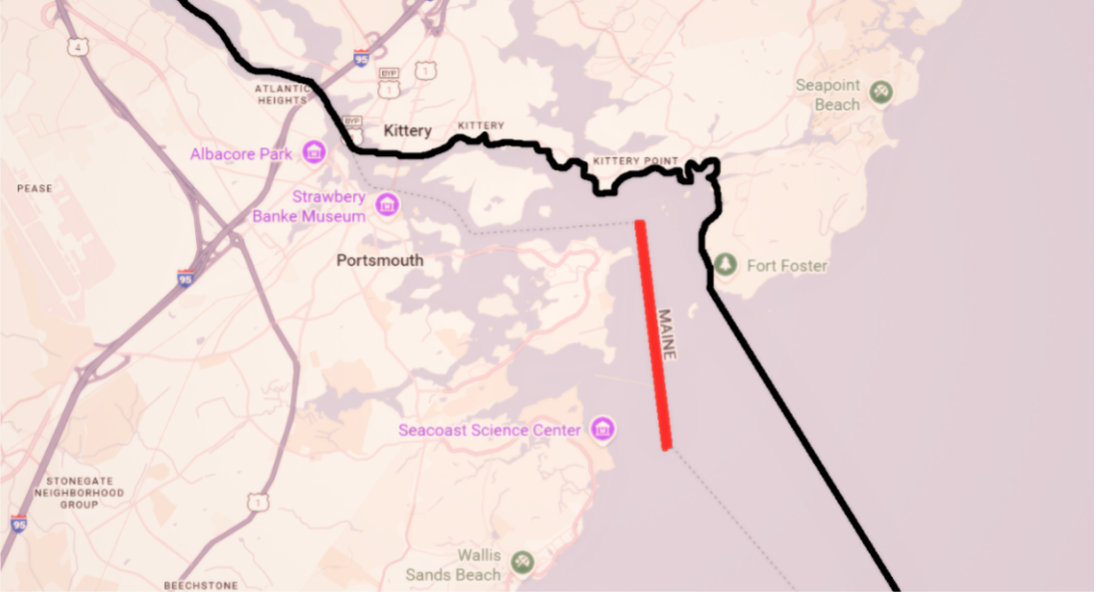

New Hampshire’s approximate historic borders are shown in black. The red line depicts the north-south lobster boundary created in 1977.

In 1901, New Hampshire arranged for the largest TNT explosion in history at the time. Henderson’s Point, part of Seavey’s Island that projected 500 feet into the inner channel of the harbor, was obstructing ship traffic—and New Hampshire collaborated with the US Army Engineers to blow it up. Nobody claimed that the island was outside of New Hampshire’s jurisdiction or that the explosion was destroying part of Maine.

In 1905, the Treaty of Portsmouth between Russia and Japan was signed on Seavey’s Island—an event still celebrated annually in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and in New Hampshire state law. The treaty’s text directly states that it was signed in “Portsmouth (New Hampshire).”

Even after the lobster disputes with Maine in the 1970s, New Hampshire took for granted that it broadly controlled the harbor and the harbor islands. In 1991, New Hampshire paid the equivalent of $ 12 million to dredge the entire harbor and create a turning basin extending up to the shores of Maine. Maine paid nothing.

How Maine Stole the Harbor Islands

In 2001, New Hampshire sued Maine to establish its claim to Seavey’s Island. In law school, I remember reading about New Hampshire v. Maine as an example of the Supreme Court’s “original jurisdiction”: a case that went straight to the Supreme Court. At the time, I imagined that the Court had performed a searching inquiry into the states’ colonial borders and decided that the historical record supported Maine. In reality, Maine got lucky.

Although the border dispute has repeatedly come before the Supreme Court, the Court has never directly confronted the historic harbor boundary in an adversarial proceeding—an inquiry Maine could not hope to withstand. This stroke of luck has allowed Maine to claim Portsmouth Harbor’s waters and islands through bluster, aggressive negotiation, and procedural chicanery without ever having to defend its weak historical claims.

The truth is that, despite the historical strength of New Hampshire’s arguments, Vacationland wanted the islands more—and it was willing to fight harder and dirtier than New Hampshire.

Beginning in the 1970s, Maine manufactured the border conflict through an escalating campaign of arresting New Hampshire lobstermen, towing New Hampshire boats, and eventually taxing Granite State lobstermen and shipyard employees.

In 1977, New Hampshire and Maine agreed to a Supreme Court consent decree to settle lobster fishing rights, drawing a north-south line in the water east of New Castle Island. Unfortunately, this agreement gave away New Hampshire waters that had never been part of Maine—apparently through the sheer incompetence of New Hampshire’s Republican attorneys. Yet the decree did not clearly address the interior harbor boundary or apportion the harbor islands.

Maine, however, had taken an inch and wanted a mile. In the late 20th century, it gradually persuaded the US Navy to credit its claims to Seavey’s Island and, increasingly, sought to tax Naval Shipyard employees. In 1997, Maine began to garnish the pay of Naval Shipyard workers, claiming that it was collecting unpaid “back taxes.”

By coincidence, as Maine was escalating its claims, then-Governor Jeanne Shaheen was on a trade mission to England, where she happened to visit an archive of colonial records in Winchester. Shaheen, who had not known the history of the harbor boundary, was shocked to see that 18th century colonial maps showed the entire harbor as New Hampshire territory. Energized, she directed the state Department of Justice to take Maine to court.

This time, New Hampshire was better-prepared than in 1977. New Hampshire’s lead counsel, Assistant Attorney General Leslie Ludtke, had a keen awareness of the historical arguments proving New Hampshire’s ownership of the harbor. Yet New Hampshire’s case was, from the start, beset by problems.

As a suit between two states, New Hampshire’s case went straight to the US Supreme Court. Yet the Supreme Court is not used to being a trial court. During the oral argument, Ludtke had no large map in the courtroom that she could use to illustrate the boundary dispute—something she likely would have had federal district court. With no overarching visual reference, the Court was clearly befuddled by the New Hampshire place names, rivers, harbors, thalwegs, and range lines.

In particular, Justice Scalia—throughout New Hampshire’s entire argument—stubbornly confused the Portsmouth Harbor with Gosport Harbor, a separate harbor 9 miles away in the Isles of Shoals. Scalia was incredulous that Ludtke would claim the whole Portsmouth Harbor given that the interstate boundary runs through “the middle” of Gosport Harbor.

When Ludtke gently tried to explain that Scalia was conflating two completely different harbors, Scalia seems to have assumed she was nitpicking. Every time Ludtke began to elaborate on the distinction, she was interrupted or pulled into other lines of questioning. Ultimately, Ludtke completed her entire argument without fully correcting Scalia’s mistake or explaining that Gosport Harbor was 9 miles from the disputed area.

Yet New Hampshire’s biggest problem was Maine’s abuse of the 1977 consent decree. The north-south boundary in the decree had been described as being in “the middle of the main channel of navigation” into the harbor. Using specific coordinates, the decree described this channel as commencing east of New Castle Island, proceeding south, and terminating to the east of Odiorne Point.

Wrenching these words out of context, Maine seized on the words “the middle” and beat them like a drum. Its motto was simple and repetitive: “quote, the middle, close quote.” Essentially, Maine argued that, because the consent decree had referred to “the middle” of a channel, the entire harbor should be divided down “the middle” as well.

New Hampshire became overextended, allowing itself to be drawn into explaining geography, history, the consent decree, and whether the decree might be set aside. The fact that “the middle of the main channel of navigation” referred to one discrete line became lost in the noise. Meanwhile, Maine’s argument was stupid yet elegant: give us half of everything.

Without ever adjudicating the historical boundary, or even deciding what borders were created in 1977, the Supreme Court held simply that New Hampshire was “estopped” from bringing its claim by the consent decree—all based on the words “the middle” in the decree.

The Court did leave New Hampshire one ray of hope: it never directly held that New Hampshire was estopped from claiming Seavey’s or Badger’s Islands in the future. Instead, its conclusion was circumspect: “we conclude that judicial estoppel bars New Hampshire from asserting that the [harbor] boundary runs along the Maine shore.”

How to Retake the Harbor Islands

New Hampshire still has strategies it can pursue to reclaim its harbor or—if not the whole harbor—at least its islands. Whatever strategies it uses, however, one thing is clear: New Hampshire must be aggressive. The sad fact is that New Hampshire lost its historic waters and islands largely because it was less assertive in defending its territory than Maine was in stealing it.

As a right-winger, I usually prefer less government and less taxes. Yet we have to admit that, paradoxically, New Hampshire’s laissez-faire attitude created the conditions for Maine to seize the harbor. While Maine was towing New Hampshire’s boats, arresting its fishermen, and taxing its workers, New Hampshire did nothing of the kind in return. This imbalance contrived an apparently bona fide dispute in which Maine appeared to occupy the high ground. By avoiding state interference in the harbor, New Hampshire naturally yielded up its territory to the more assertive state.

To undo this mistake and retake the harbor, New Hampshire should adopt a coordinated strategy involving the legislature, the executive branch, and state law enforcement.

Last year, the New Hampshire House passed HCR 8, a resolution sponsored by Rep. Joseph Barton. This resolution would, among other things, ask President Trump to change the official duty stations of Naval Shipyard employees from Maine to New Hampshire—freeing Granite State shipyard workers from Maine income taxes and reviving New Hampshire’s historic claim to the harbor. Unfortunately, the resolution was not acted on by the Senate.

This year, Rep. Barton has reintroduced the resolution as LSR 2485. This time, Granite Staters should call on the Senate to pass the resolution. Whether the Senate acts or not, Governor Ayotte can lead the way by directly lobbying President Trump to order the Navy to change the duty stations.

Granite Staters in the Trump administration, including Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt, should also lobby the president. Leavitt can point out that, among other things, changing the duty stations will help bolster her campaign if she decides to run for Congress again in the future.

Secondly, the legislature should pass a Fort Sullivan Act, implementing a package of reforms to revive its claims over the harbor. RSA 22:2, for example, can be amended to reassert and directly clarify that Rockingham County includes the harbor islands and the entire harbor. New Hampshire law enforcement and state agencies should be directed to aggressively enforce New Hampshire law in the harbor and on its islands—the same thing Maine did in the late 20th century.

Finally, and most importantly, a bill should direct the New Hampshire Department of Justice to relitigate New Hampshire’s case before the US Supreme Court. There are at least a few claims the DOJ can still pursue.

First, and most obviously, the DOJ should argue that New Hampshire v. Maine was egregiously wrong and should be overturned. Even if New Hampshire is bound by the 1977 consent decree, the 2001 Court still erred in treating the entire harbor, rather than a distinct north-south line, as the subject of the decree. If Michigan and Wisconsin agreed that their boundary was “in the middle of Lake Michigan,” that would not entitle Wisconsin to claim half of Lake Superior as well.

Justice Scalia’s persistent error in the oral argument only underscores the fact that the Court did not know what it was doing and did not treat New Hampshire’s sovereignty and history with the gravity it deserved.

Next, the DOJ should argue that, even if the Court does not overturn New Hampshire v. Maine, it should still declare that Seavey’s and Badger’s Islands belong to New Hampshire. The 2001 case technically held that New Hampshire is estopped “from asserting that the [harbor] boundary runs along the Maine shore.” Even if New Hampshire must forfeit some of its historic waters under the 1977 consent decree, this should not mean that we lose our historic islands as well.

Finally, New Hampshire might try a collateral attack, arguing that Maine has been unjustly enriched by New Hampshire’s financial investments in the harbor. As late as 1991, Maine sat back and watched while New Hampshire unilaterally financed harbor renovations. If Maine is now allowed to claim half of the harbor, Maine should have to pay New Hampshire back.

While the amount of damages might be relatively small—Maine’s share of the $12 million New Hampshire spent dredging a turning basin, for example—this argument might underscore the absurdity of letting Maine redraw state boundaries after 300 years.

For a state as proud as New Hampshire, it is remarkable, and unfortunate, how paltry a fight was put up to keep our harbor—and how little we have done to reclaim it. Nations much newer and weaker than New Hampshire have gone to war over less.

As one of the original Thirteen Colonies, New Hampshire brought the United States into existence. In fact, if New Hampshire had voted against ratifying the Constitution in 1788, the nation as we know it today might not exist. We should never passively allow federal agencies, another state, or anyone else to compromise the sovereignty or territorial integrity of the Granite State.