Eastern Equine Encephalitis is nasty but rare. The fatality rate varies, depending on who you cite, but this 2023 paper puts it at around 30%. A more significant number of those infected suffer neurological damage that does not result in death. When a case pops up, people get antsy, with good reason. A 41-year-old NH man died of it this season, and the local response in Oxford, Mass, went wide as everyone with a blog or substack added their two cents, including me.

It was late August, and in the weeks between then and now, things seemed quiet. Perhaps other shiny objects have diverted the attention of the commentariat horde, so did the EEE threat disappear? Maybe a bit of background first.

Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) is one of the most severe arboviral encephalitis affecting America. Currently considered an emerging disease showing consistently increase incidence across a wider population. In the United States, between six to eight cases are annually reported, predominantly between May through October, mostly in Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Wisconsin, and New Jersey

This from the 2023 paper I cited above.

Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) is an arbovirus from the Togaviridae family, genus alphavirus. Maintained by a cycle between birds and predominantly Culiseta melanura mosquitoes associated with freshwater hardwood swamps.[5] Recent data suggest other mosquitoes species also involved in EEBV transmission include Coquillettidia perturbans, Aedes cinereus, and Aedes canadensis.[6][7] The mosquitoes get infected and transmit EEV during blood feeding to passerine (tree-perching) birds and opportunistic mammals, reptiles, or amphibians. This virus can escape its usual reservoir to infect dead-end hosts (humans, swine, equids, pheasants).

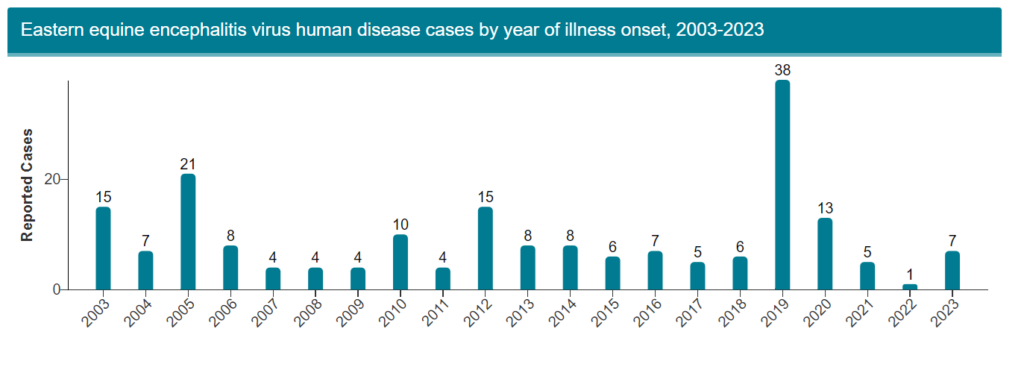

Dead-end hosts are (apparently) reservoirs from which additional bites do not typically affect new-feeding mosquitos, so people do not normally aggravate the spread if fed upon after infection. And despite the recent uproar and concern, the current number of cases is neither an exception nor indicative of anything climate-related. CDC reports 10 cases nationally in 2024. That’s likely to rise (It is mid-September, and mosquitos are active well into October, weather permitting), but it would be surprising to see the case count exceed the historical high of 38 in 2019.

This is (also, apparently) not a good indicator of prevalence. Again, deferring to the cited research,

Human arboviral disease, when symptomatic, can be divided into three different syndromes: Febrile systemic illness (seen in uncomplicated Dengue fever), Hemorrhagic fever (seen in dengue hemorrhagic fever and yellow fever) and encephalitis. This last category includes EEE but also Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis, and La Crosse encephalitis.[8] Nearly 96% of infected patients remain asymptomatic. Those with symptoms usually start with non-specific symptomatology, fever, headache, malaise, chills, arthralgias, nausea, and vomiting also reported.[8] Less than 5% of the infected population will develop meningitis or encephalitis.

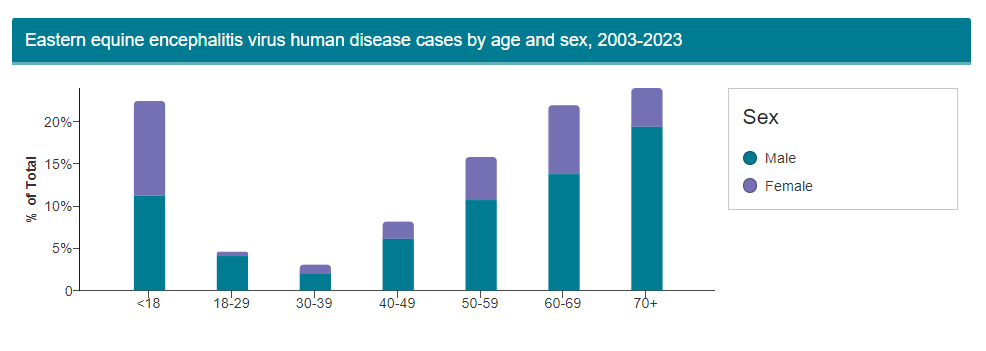

Bites by infected mosquitoes are something of an encephalitis Russian Roulette, with the majority of reported infections (at least in the CDC Data) occurring in individuals under 18 and those over 50, more so in older men than older women.

I’m guessing this has more to do with opportunity than age or sex and then general overall health. If you are outside more, the odds of exposure increase. Younger people might be outside more, and the elderly have preexisting comorbidities that make them less resistant.

I’m not an expert, and per our FAQ, nothing we do is considered professional advice, but one line in that research paper caught my eye: “This virus has also been considered a potential bioterrorism weapon given its airborne transmission.” Nowhere else in the research does it mention airborne transmission.

I wonder if NIH funding gain of function research into aerosolized Triple E?