Confirmation bias is something we all need to be wary of. We all tend to look for things that support our presupposed notions. It’s a dangerous psychological trap that it takes some intellectual discipline to combat. It requires listening to and understanding counterarguments. This is not a discipline practiced very often – if ever – in our State House these days.

Case in point happened on February 8th in the Ways & Means Committee when Cristobal Young from the Cornell Department of Sociology was called in to testify about his book, The Myth of Millionaire Tax Flight, in a flagrant attempt to provide some confirmation bias to the committee’s desire to pass a “millionaire’s tax” – a 3 percent surcharge on Vermonters’ incomes over $500,000 (H.828).

Young’s presentation, in a nutshell, was that, yes, high taxes will chase away some high earners, but it’s an insignificant number. So, go for it! At his conclusion, committee chair Emily Kornheiser (D-Brattleboro) gushed, “Thank you very much, you’ve made an incredibly, I don’t want to say compelling case because you’re just sharing the research with us, but I really appreciate your sharing the data with us …. I think in our work it’s really hard to separate anecdote from data, and you have laid out the data incredibly well.”

Yeah. About that. Here’s the problem with the research and the data….

Young’s book was published in 2017, before Covid lockdowns and the explosion of remote work options. And, before the 2017 federal tax reform law that ended State & Local Tax (SALT) deductions for federal taxes, effectively raising taxes on wealthy individuals in high tax states – like Vermont – and cutting them in low tax states like Florida, Texas, New Hampshire. The SALT reform forces those who choose to live in high tax states to bear the cost of that tax burden themselves rather than pass it on to federal taxpayers across the country.

The data presented in Young’s slide show was from 1999-2011, 2000-2003, 2005-2014 – when the internet was in its infancy. And, it was primarily focused on New Jersey, where working millionaires are largely tethered to the New York financial markets, and California with Silicon Valley and Hollywood. So, let’s just say that this forty-five minutes of committee time was, notwithstanding Chair Kornheiser’s early Valentine’s expressions of schoolgirl love, largely irrelevant. Except for the fact that it served as confirmation bias for the tax and spenders.

A more up to date study done in July 2023 by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth – hardly a bastion of right wing ideology – echoed some of Young’s conclusions that high earners tend to be more firmly rooted in the communities where they are generating their wealth (ie. New Jersey based Wall Street millionaires, who, not for nothing, are fleeing even higher taxes in New York City) and can’t realistically pull up stakes. Other factors that keep wealthy people in place and putting up with abusive tax policies are children in school, friends, family, and, let’s face it, moving is a hassle. All true.

However, they did note, “… the [2017 SALT] tax reform did not cause greater numbers of millionaires to migrate. But for those already moving anyway, tax reform played a role in where they moved. In other words, taxes do not affect the decision to move, but, conditional on moving, they do influence the choice of destination—making low-tax states incrementally more attractive.” Vermont is a “destination” state. Which begs the question, are the millionaires in Vermont people who make their money here and are “stuck”, or people who moved here with their money? Church Street not being Wall Street, I highly suspect it’s primarily the latter. And thus, by implementing a millionaire’s tax will we be discouraging wealthy retirees or now-free-to-be-remote working millionaires from choosing Vermont as a destination. This would be bad tax policy for us.

The Washington Center’s research also obliterates Young’s stale assumptions about the “stickiness of places” by pointing out, “the pandemic disrupted almost every socioeconomic factor that ties people to places. Offices and schools closed their doors and moved online. Urban amenities were shuttered. And face-to-face contact became a public health problem. Many homes and apartments felt too small for shelter-in-place orders. The pandemic was an occasion to rethink the geography of work and life, especially for top earners, who could work remotely from anywhere.” Uh, yeah. That.

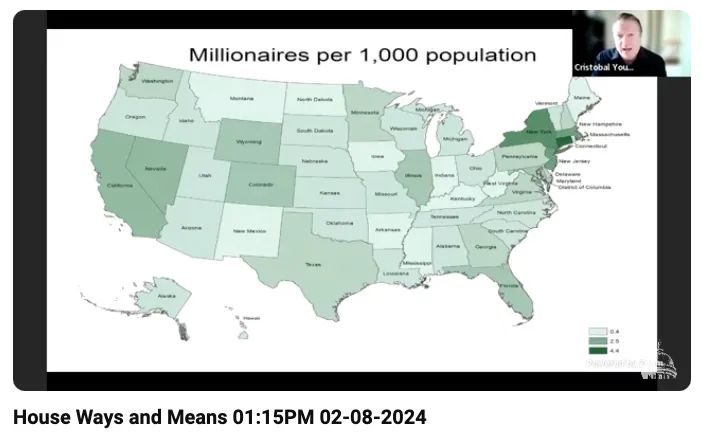

Young also shared a state-by-state map of where millionaires are concentrated, and one of the states painted with a very light shade of green, a very low percentage of population, was Vermont. So, while it is true some, perhaps many, millionaires may be stuck in places with high taxes because the benefits of economic opportunity for them outweigh the costs, Vermont isn’t one of those places. A point entirely ignored by the presenter and the committee.

Lastly, Young advised lawmakers to stick it to older, wealthier taxpayers and focus on policies that attract young, mobile workers who will be the millionaires of tomorrow. All well and good regarding the young and productive, but, as CNBC points out in Young, rich workers are fleeing New York and California – here’s where they’re going, the states attracting these folks are places with tech and/or financial hubs, which Vermont does not have, and/or low/no income tax states like Florida, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Texas, which Vermont is not. Legislators can’t change that first factor, but they can change the latter! Or not.

So, if we don’t have a lot of millionaires to begin with in Vermont, they are less “stuck” here, and they already provide a disproportionately high proportion of our income tax revenue, how many can we really afford to lose? And how many can we afford to repel? We need good information to form good policy, and our elected representatives are not seeking that out. Too often they actively avoid it.